Berlage’s Heritage Thrown to the Lions? The Story of Gedung Singa in Surabaya and a Forgotten Travel Diary

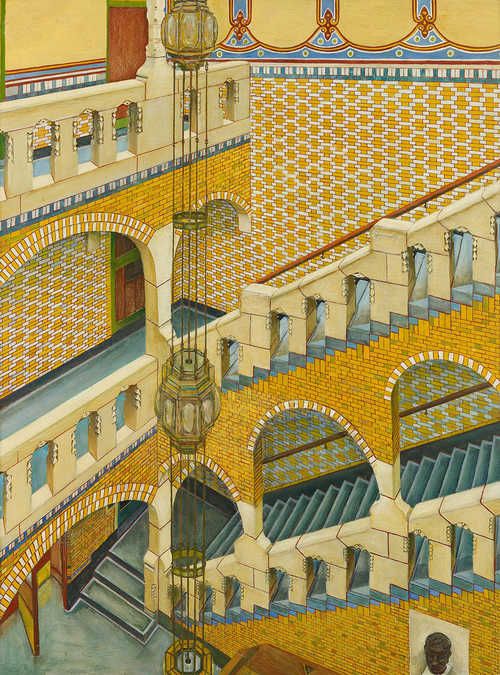

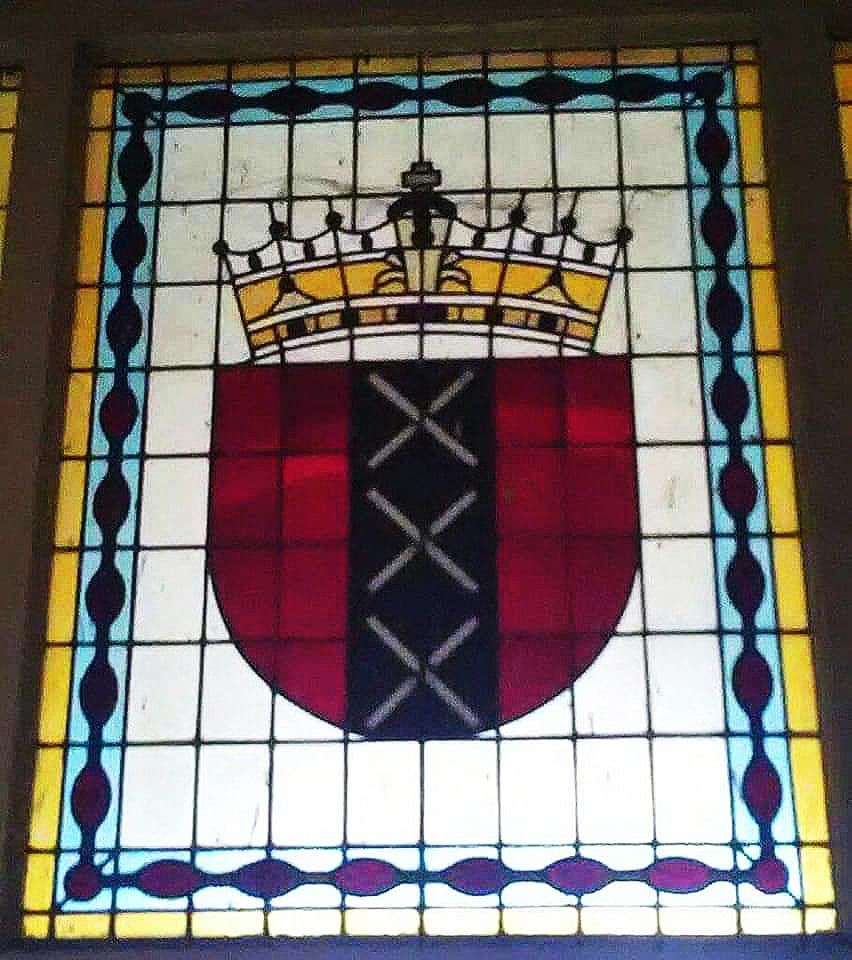

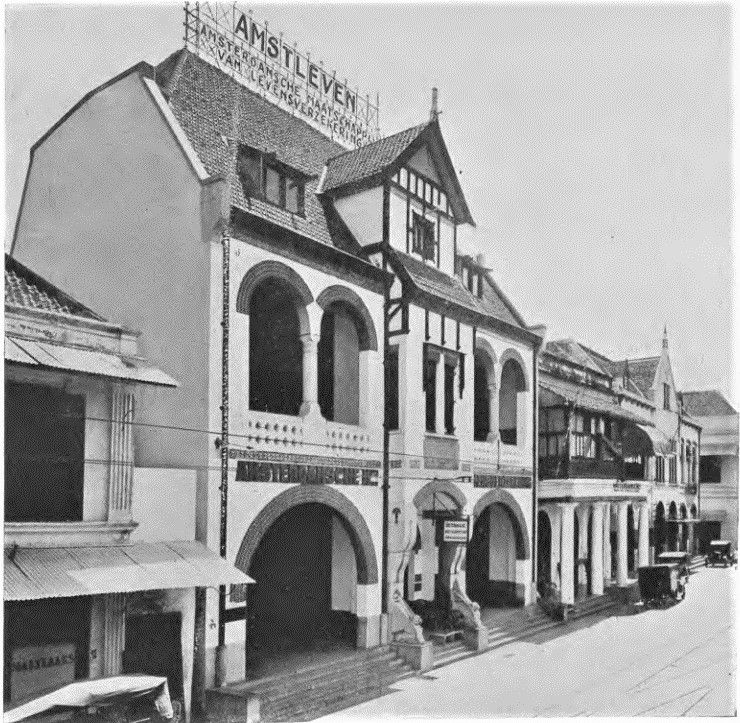

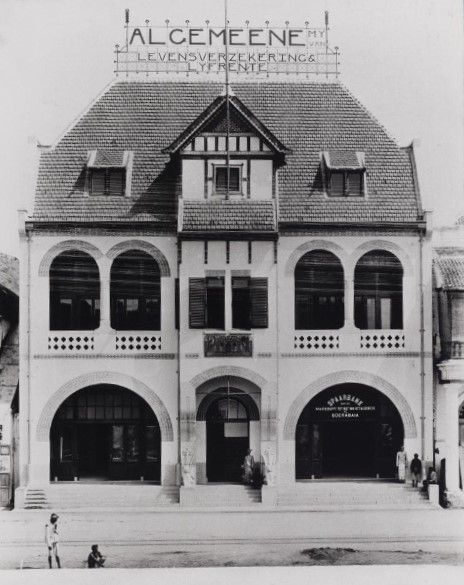

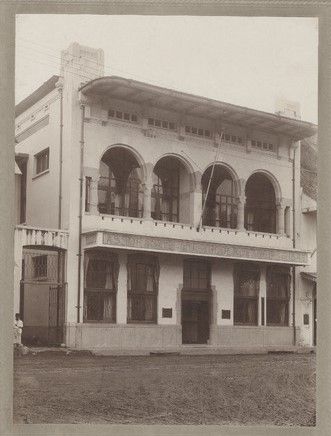

Modern Dutch architecture has one very iconic hero: Hendrik Petrus Berlage (1865 - 1934). Few people know that his architectural legacy also includes two buildings in Indonesia, dating back to when the archipelago was a Dutch colony. From his studio in Amsterdam, Berlage designed office buildings for two insurance companies: ‘De Nederlanden van 1845’ in Jakarta and ‘De Algemeene’ in Surabaya. Boasting brick arches and a colourful glazed tile tableau, Gedung Algemeene—better known as ‘Gedung Singa’ after the two ‘lions’ (singa) at the front—is a prominent eye-catcher in Kampung Eropa, Surabaya’s colonial city centre. Yet, somehow, this exceptional property has skipped Surabaya’s recent heritage revival; Gedung Singa has been ignored for years, is largely overgrown and surrounded by controversy. It recently became the subject of a fierce community outcry when contractors were a tad bit too reckless in whitewashing the façade, lions included, turning the ferocious pair momentarily into sea lions.

The error was quickly rectified, but the company that owns the building remains under the radar for now, while rumours have it that Gedung Singa will soon be back on the market once again. An opportune moment to dive into the history of the building and its creator, H.P. Berlage, to explore how knowledge of the past can help decide a future for this unique piece of Netherlands-Indonesian heritage. We dug through archives and found that the master architect left a legacy in Indonesia about so much more than his buildings in Jakarta and Surabaya.

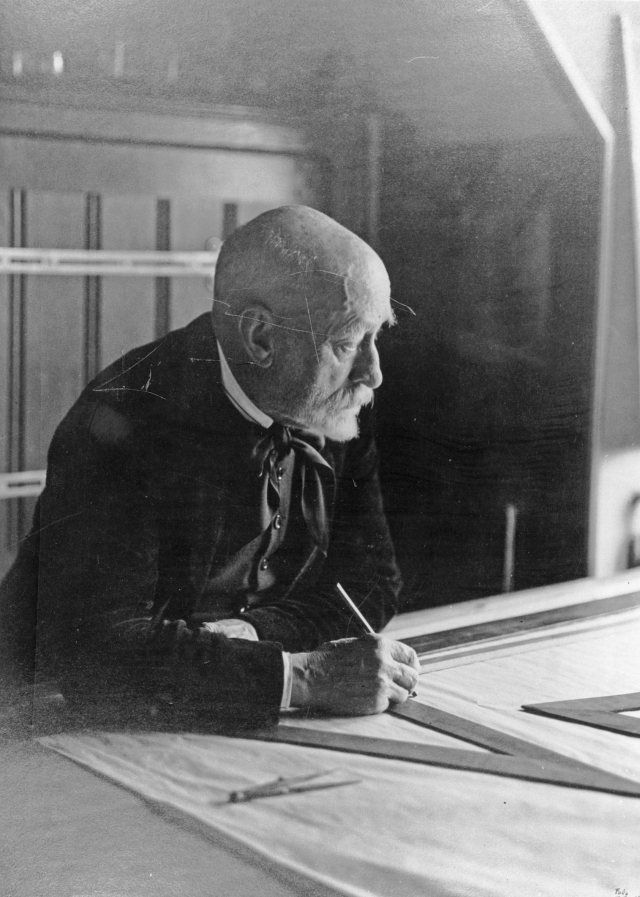

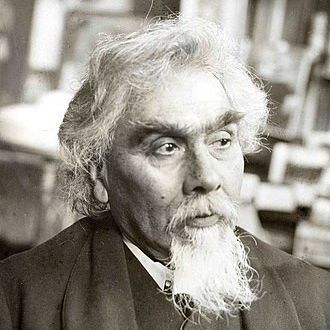

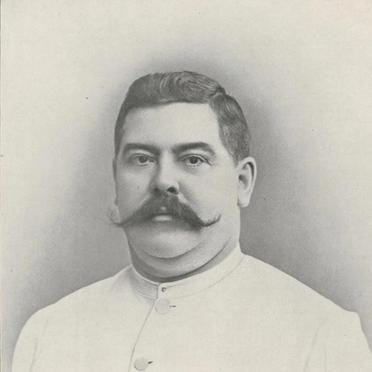

Berlage: the ‘father’ of Dutch modern architecture

Berlage shot to fame with his Beurs van Berlage, the Amsterdam Stock Exchange building, a prime example of his characteristic clean design. Built between 1898 and 1903, this building was a game changer in the Dutch capital. At a time when many architects were looking to the styles of the past, Berlage’s design with rectangular modular shapes, honest brickwork and exposed construction frames was widely considered the starting point of the modernist movement in the Netherlands. In 1999, Berlage’s Beurs was included in the Union Internationale des Architectes list of the 1,000 most important buildings of the 20th century. As of today, it still is one of the most iconic buildings in the city centre. Berlage’s architectural legacy also includes St. Hubertus Hunting Lodge in National Park De Hoge Veluwe, The Netherlands, the Holland House in the City of London and the purpose-built Art Museum in The Hague, The Netherlands. The latter is widely regarded as his greatest masterpiece. As the ‘Father of Modern architecture’ in the Netherlands, Berlage continues to inspire contemporary architects.

But Berlage was more than a master builder: he was an artist, a social commentator and a philosopher. His designs—as much celebrated as they were controversial—had a strong cultural and political purpose with a sense of community at heart, a fusion of function and spirit that he coined ‘practical aesthetics’. He was intrigued by the relationship between social and spatial order, thoughts he manifested in Amsterdam’s early 20th-century urban expansion plan Amsterdam-Zuid—still one of the city’s most sought-after neighbourhoods—as well as an impressive series of essays and spectacular ideas for noble monumental buildings as ‘an ode to lost virtues of community and social equality’. His austere design philosophy and admiration for the socialist ideals of the Arts and Crafts movement are recurring themes in his work.

In a way, Berlage used his architectural designs as a ‘social laboratory’ to express his views on society. For example, in the making of the Amsterdam Stock Exchange building, he was known for pushing his client’s agenda to create a sum that was bigger than its parts. He wanted the building to be a ‘gesamtkunstwerk’, a collaborative and comprehensive effort where the exterior and interior are one, and the architect oversees the building's totality: shell, accessories, furnishings, and public space. In his philosophy, different art disciplines would form an equal unit, a community effort to create a healthy working environment but also to stimulate people's spiritual well-being. He collaborated with many prominent artisans who created sculptures, tile tableaus, stained glass windows, carpets and even furniture for the building.

Berlage’s Indonesian legacy: Gedung Singa in Surabaya

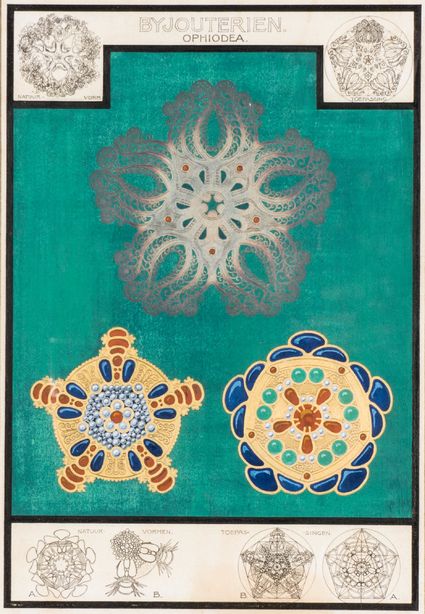

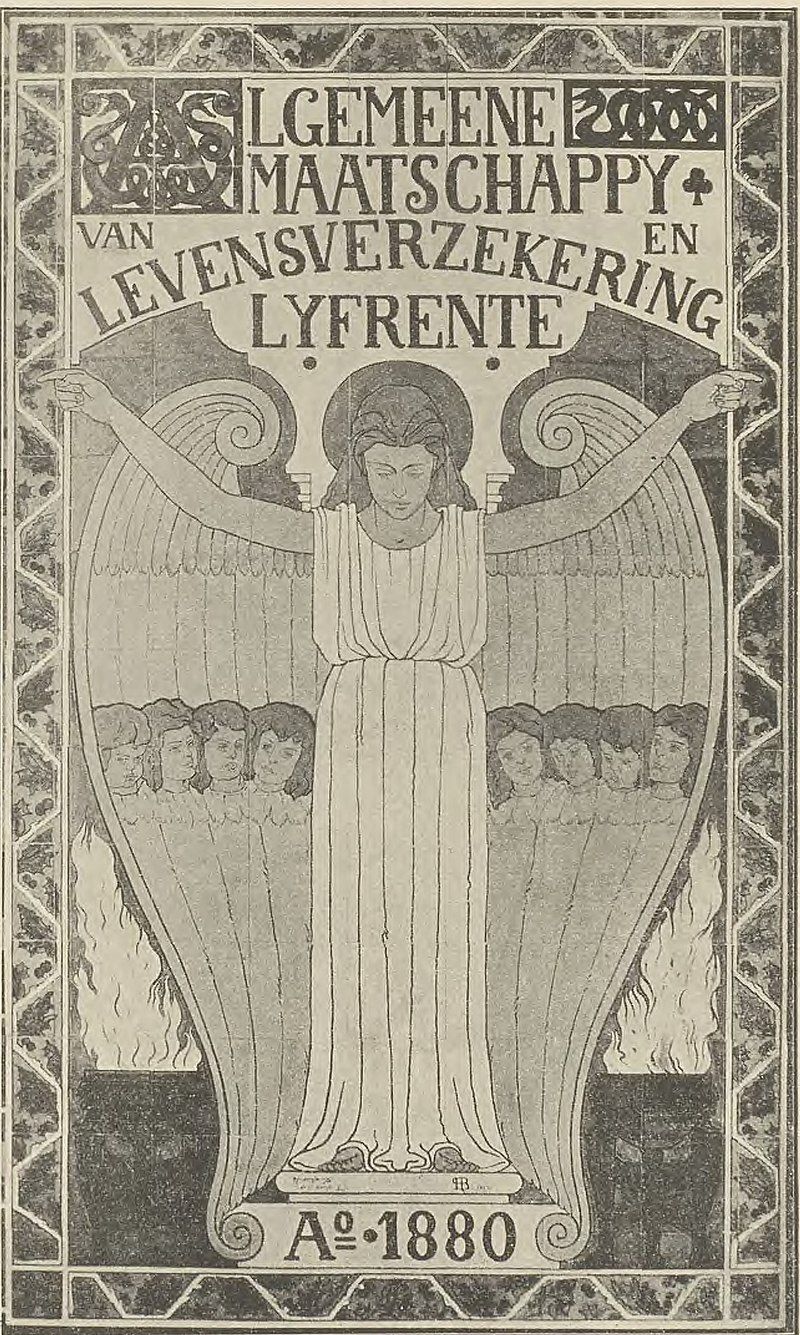

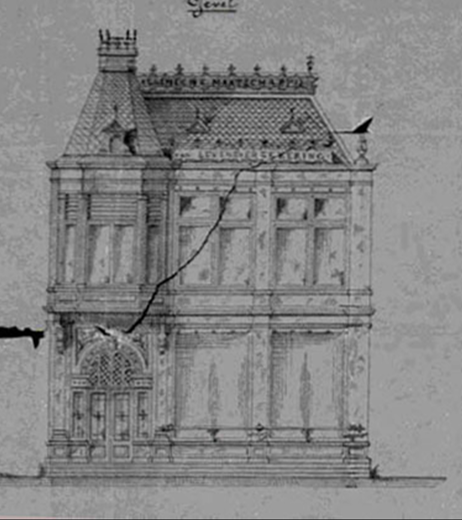

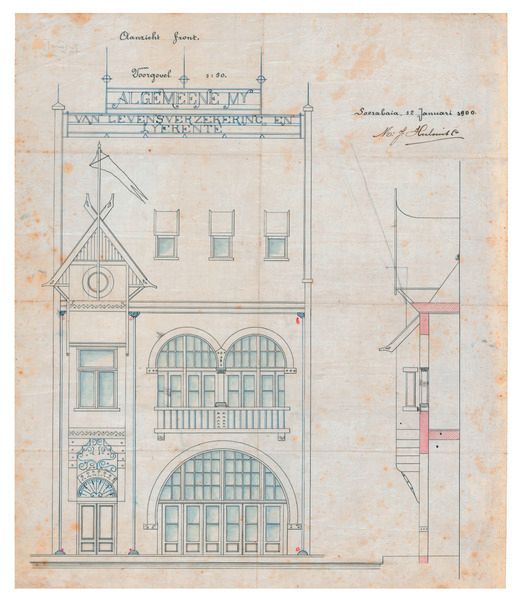

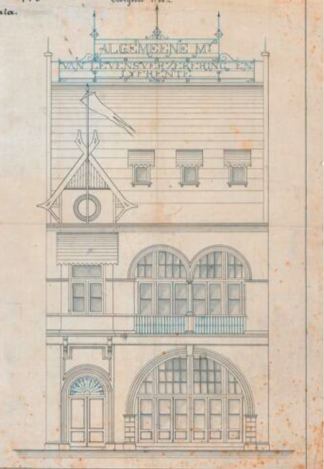

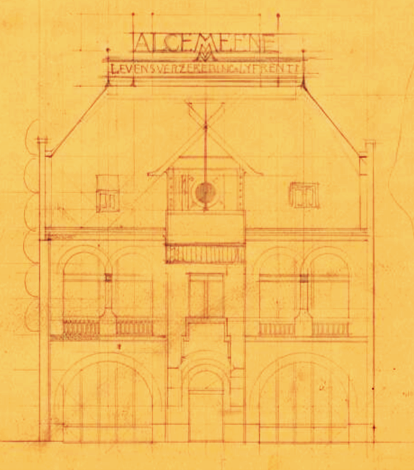

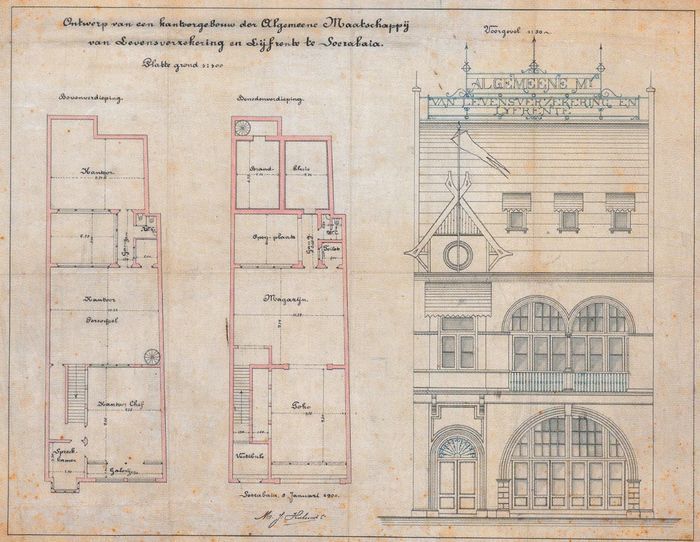

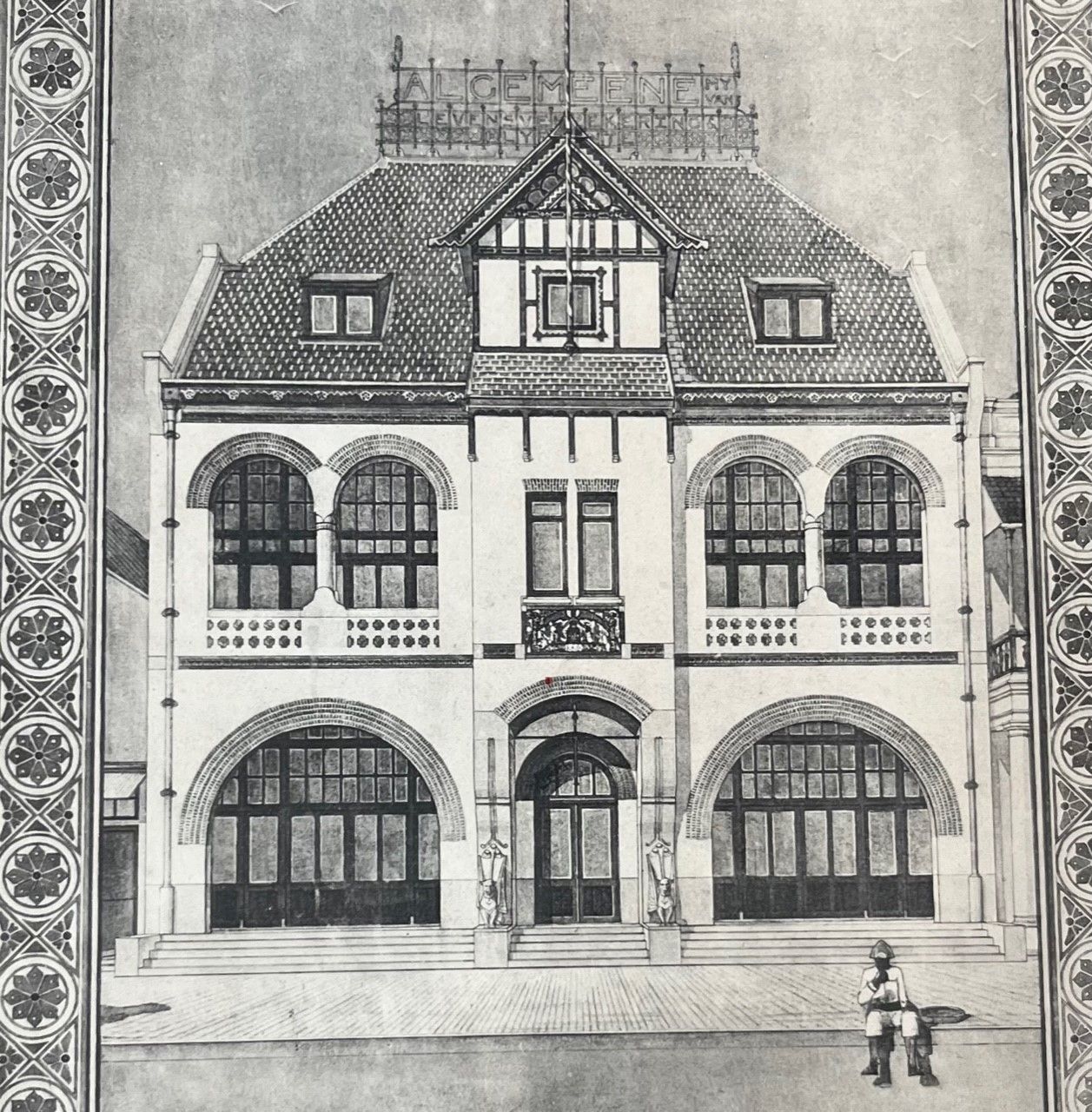

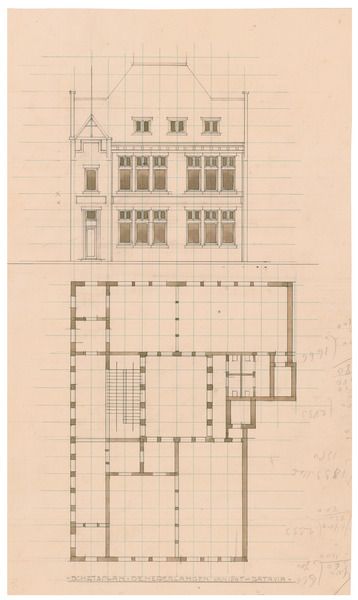

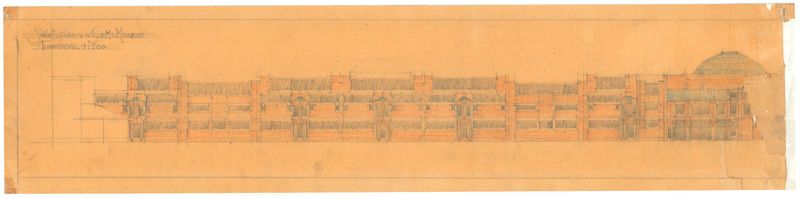

In 1898, around the same time as he was working on his designs of the Amsterdam Stock Exchange building, Berlage was asked to comment on a design for a new office for the ‘Algemeene Maatschappij van Levensverzekering en Lijfrente’ in Surabaya. As the designer of the company’s Amsterdam headquarters (opposite de Beurs building) and 'in-house-architect', they wanted him to vet the style of their physical presence in the Indies. The design was by Marius J. Hulswit, a contractor who learned the ropes at the office of Pierre Cuypers, known for the Rijksmuseum and Amsterdam Central Station. Hulswit moved to the Dutch East Indies in 1893 and made a name for himself with projects like the Surabaya Palace of Justice.

I can not but reject this kind of European design. The façade resembles that of a villa-like shophouse in a small community designed by a small architect.

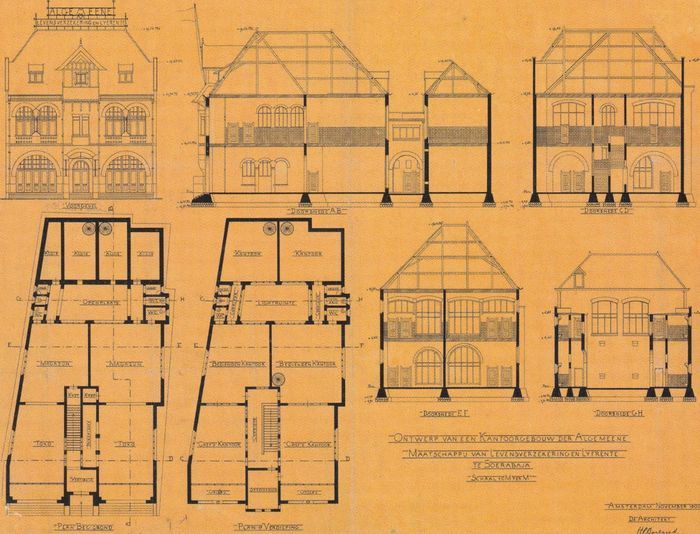

When Hulswit submitted his drawings, Berlage dismissed them as ‘too European’ and sent him back to the drawing board. Even when Hulswit sent a revised version in 1900, Berlage was not satisfied and ended up completely redrawing it. He even incorporated an adjacent plot to make the building symmetrical. Eventually, Hulswit decided to take his hands off the project. Although he was invited to supervise the construction, he politely declined and jumped on the opportunity to work on the new Cathedral of Jakarta instead.

That’s the short story of how Gedung Singa ended up in the books as ‘a Berlage’. Also known as Gedung Singa, ‘the house with the lions’, it was the only modern architectural building in town at the time, distinctly different from the classical, white-painted buildings in Surabaya’s colonial city centre. Gedung Singa was quick to become one of the city’s most prominent office buildings along the Willemskade, now Jl. Jembatan Merah.

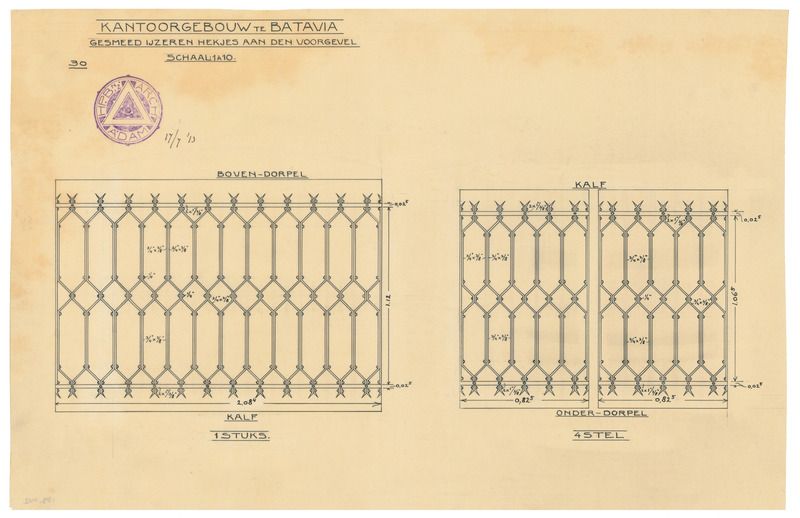

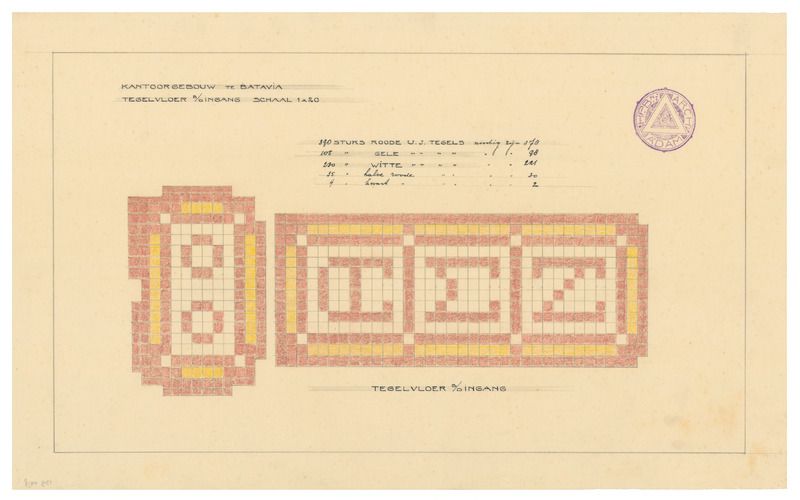

The building boasts quite a few markers of Berlage’s signature style. Take the brick arches and the ornamental pillars, two, typical ‘Berlagian’ elements. and as a result. Also the building’s interior is jazzed up with tiled walls and exposed brick arches. Much like the Amsterdam stock exchange building, Gedung Singa was a collaborative effort as well. Berlage invited some of his close colleague artisans to contribute to his design.

The eye-catching stone ‘lions’ and the glazed tile tableau on the building’s façade were created by Joseph Mendes da Costa and Jan Toorop, two of his peers who also worked on the Stock Exchange project. Mendes Da Costa designed the two ‘lion’ sculptures to guard the entrance and safekeep the possessions inside. The tile tableau by fellow artist Jan Toorop portrays two mothers with children, one European and one Indonesian with a protective figure in the middle, symbolising the importance of having insurance.

An interesting fact about Toorop, one of the most international and influential artists in the Netherlands around the turn of the 20th century, is that he had Indonesian roots: he was born in Purworedjo, a town on the island of Java. Toorop who was known for his unique symbolist style, was proud of his roots. In an interview in 1925 he emphasised: “One cannot take away the Indies in me; the foundation of my work is the East”. Javanese motifs and woodblock prints as well as other cross-cultural influences are prominently featured in his work. Later in life, he often turned to Catholicism for inspiration.

One cannot take away the Indies in me; the foundation of my work is the East.

The three symbolic tile tableaus Toorop created for the stock exchange building, titled ‘Past, Present and Future’, ended up becoming the building’s signature pieces. Like other interior design elements in the ‘cradle of capitalism’, the tableaus contained nudges to current social issues, such as the working conditions of labourers and women’s emancipation. It seems the two artists bonded in their social commentary to challenge stock traders to reflect on the cycles of time and society; it makes one wonder what the design brief would have been for this symbolic mosaic in Toorop’s native country.

As for Hulswit, in 1910, he established an architecture agency in Batavia (now Jakarta) with Eduard Cuypers, the cousin of, indeed, Pierre Cuypers.) Their firm specialised in traditional classical designs, a style sought-after by clients looking to build banks, hotels, insurance and trade companies in the colony. The designs were made at Cuypers office in Amsterdam while Hulswit oversaw implementation on the ground. A few years later, Arthur Fermont joined the partnership and Hulswit-Fermont-Cuypers would end up constructing more than 150 buildings in the archipelago, including major projects such as the headquarters and branch offices of De Javasche Bank in Indonesia. Hulswit passed away in 1921, but the firm Fermont-Cuypers continued to practise until 1958.

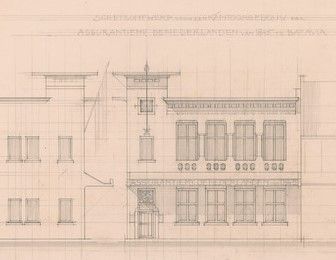

Interestingly, in 1913 Hulswit oversaw the construction of a new office building at the Binnen Nieuwpoortstraat (now Jl. Pintu Besar Utara) in Batavia for another insurance company. The architect of the building? None other than H.P. Berlage.

Gedung ‘De Nederlanden van 1845’ in Jakarta

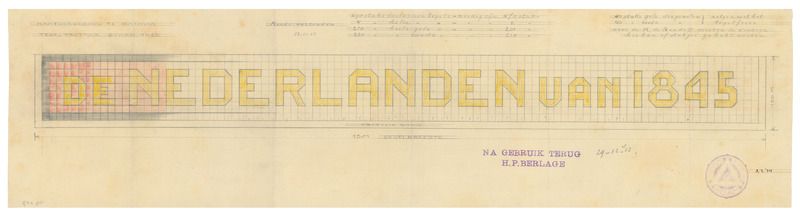

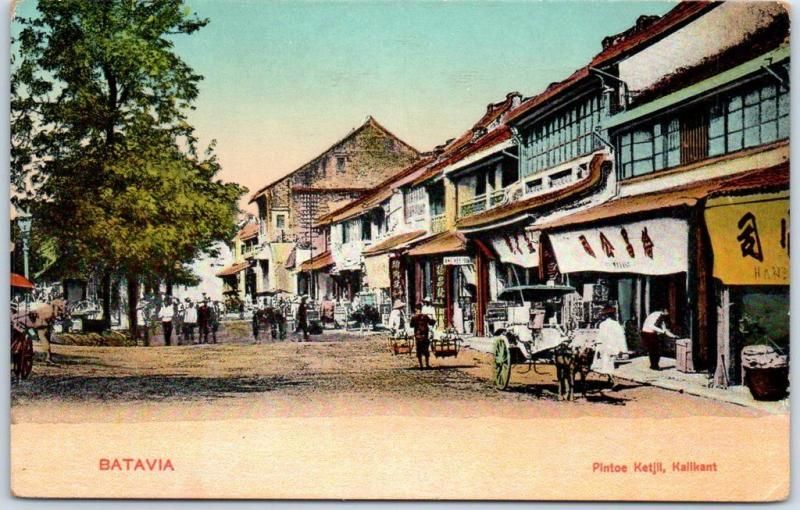

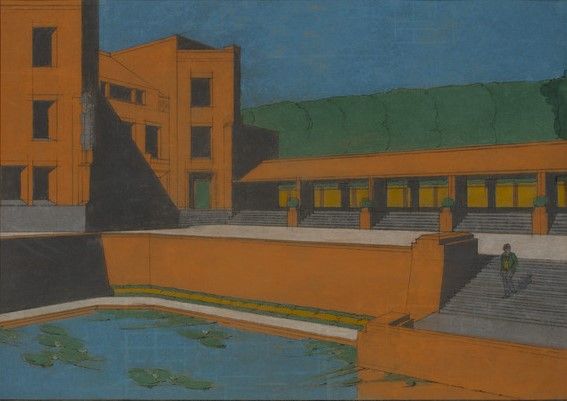

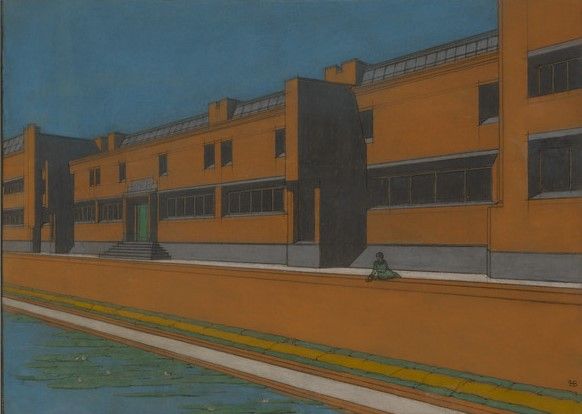

Berlage's second Indonesian legacy is located in the old city centre, the Kota Tua of Jakarta. This office building for the Dutch insurance company ‘De Nederlanden van 1845’ is in a cobblestoned side street, just off the central square Taman Fatahillah. Berlage had designed several offices for this company, and so, they asked him to design their Batavia headquarters as well. The recession was looming in Europe, and like many ambitious architects of his days, he embraced this opportunity wholeheartedly. Berlage designed it in 1913, when Batavia was the thriving commercial hub and wealthy capital of the Dutch colonial empire.

The compact building unmistakably carries Berlage’s style signature in the then-popular deco style featuring two small towers and an overhang to shield the building from the heat. The original building had a colourful mosaic tile tableau carrying the company’s name, which did not survive the two renovations that took place after the property changed hands to Assuransi Jasindo, the successor of the Nederlanden.

Berlage’s Indonesian buildings: inspiring or inefficient?

Much like Gedung Singa, Gedung ‘De Nederlanden van 1845’,, was designed by Berlage's studio in Amsterdam and the blueprint was sent to Batavia. Berlage himself had not set foot in the colony—yet. But more on that later. In the local architecture community, Berlage’s building was met with controversy: C.P. Wolff Schoemaker, the leading architect of those days, dismissed it as “inefficient and totally unsuited to the tropics”. The editors of Dutch magazine ‘Het Bouwkundig Weekblad’ ‘The Architectural Weekly’), however, referred to it as a “credible specimen of modern Dutch Indies architecture”.

Architectural historians generally concur that these Indonesian buildings do not carry significant weight in Berlage's body of work. In the development of East Indies architecture, they were not perceived as innovative either, unlike Berlage's groundbreaking design for the stock exchange in Amsterdam, which reshaped architectural perspectives in the Netherlands. Yet, retrospectively, architectural historians like Huib Akihary and Pauline van Roosmalen conclude that Gedung Singa did inspire pioneering architects in the colony, among whom Piet Moojen, who designed the famous Kunstkring in Batavia. S. Snuyf and J.F. van Hoytema, two architects who held leading positions within the Department of Public Work”, and whose robust designs included the Medan Post Office and the Department of Home Affairs in Batavia, were also influenced by Berlage

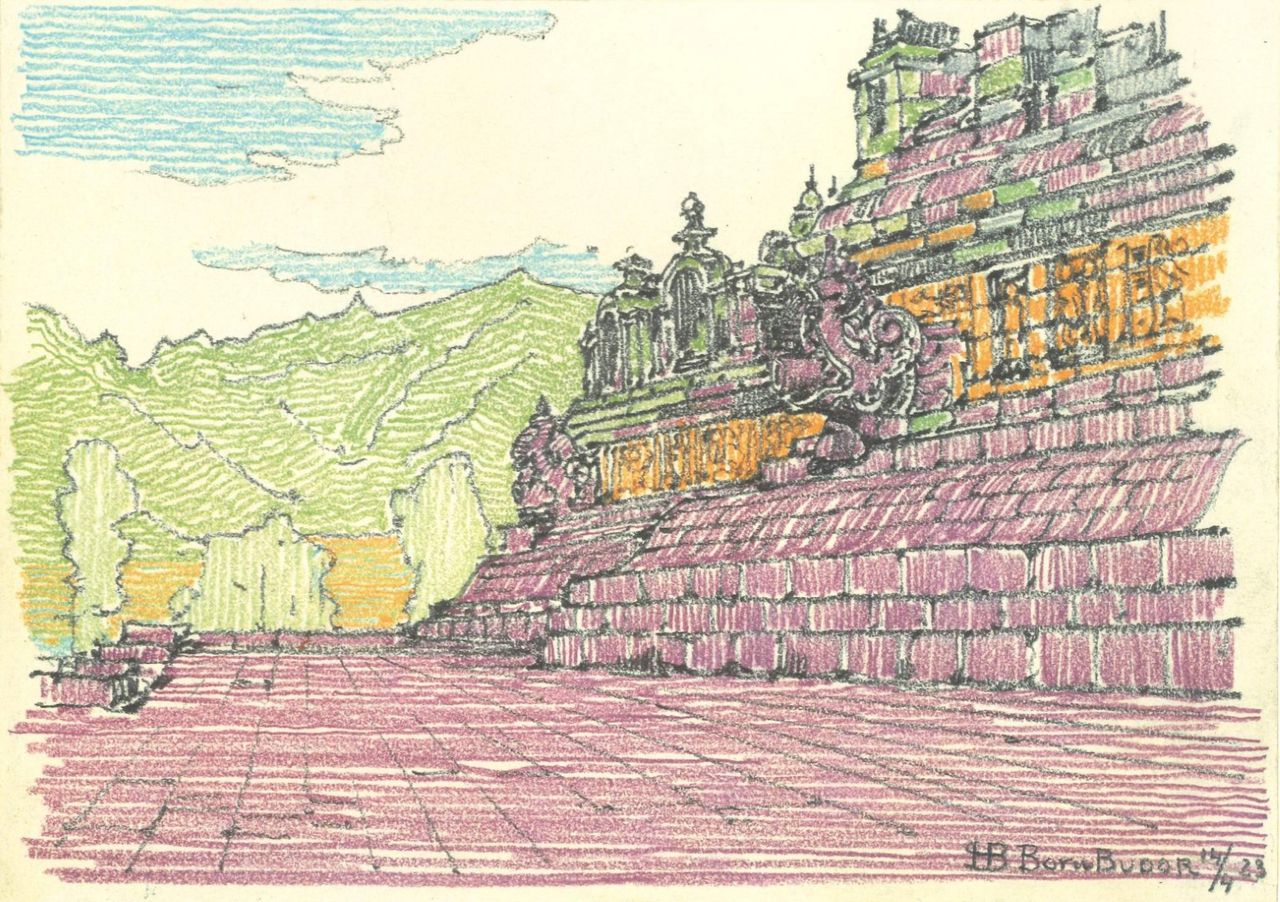

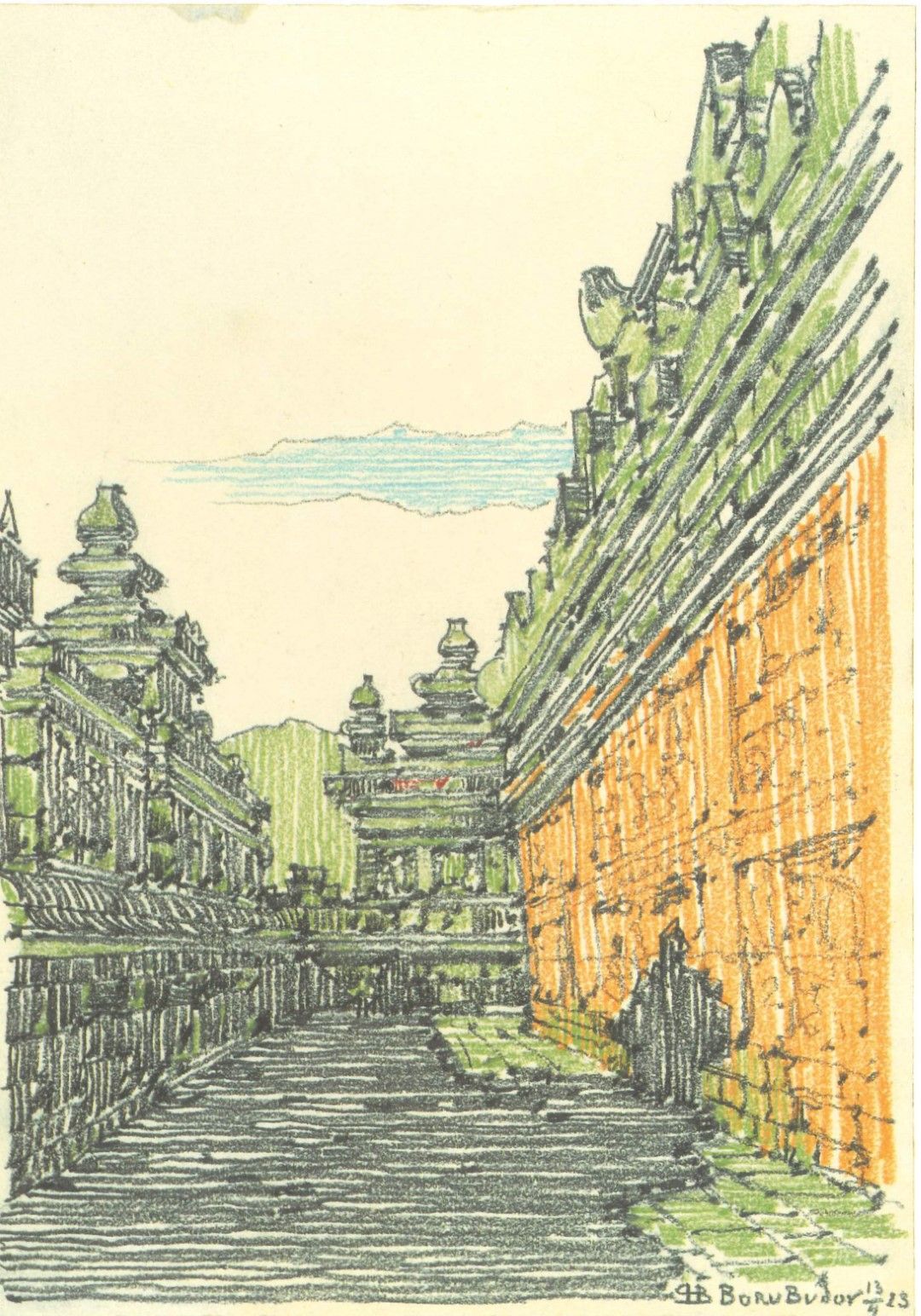

Berlage’s Indische Reis; a journey to a far-away colony

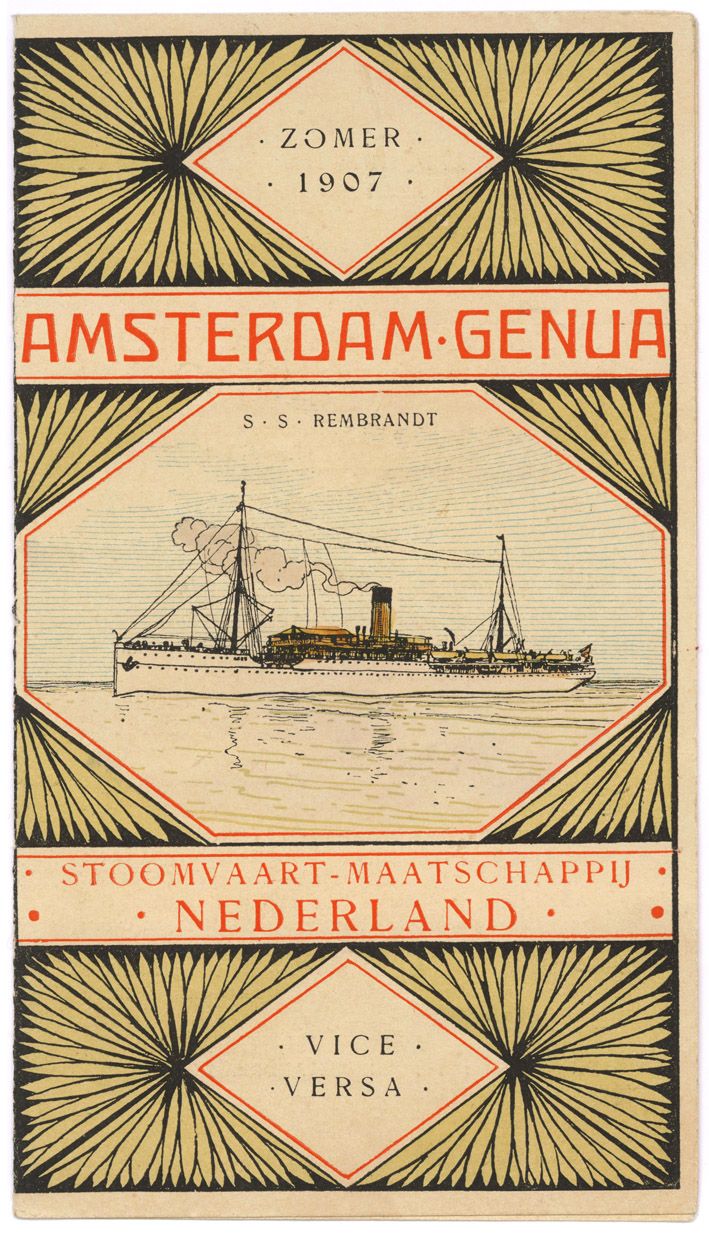

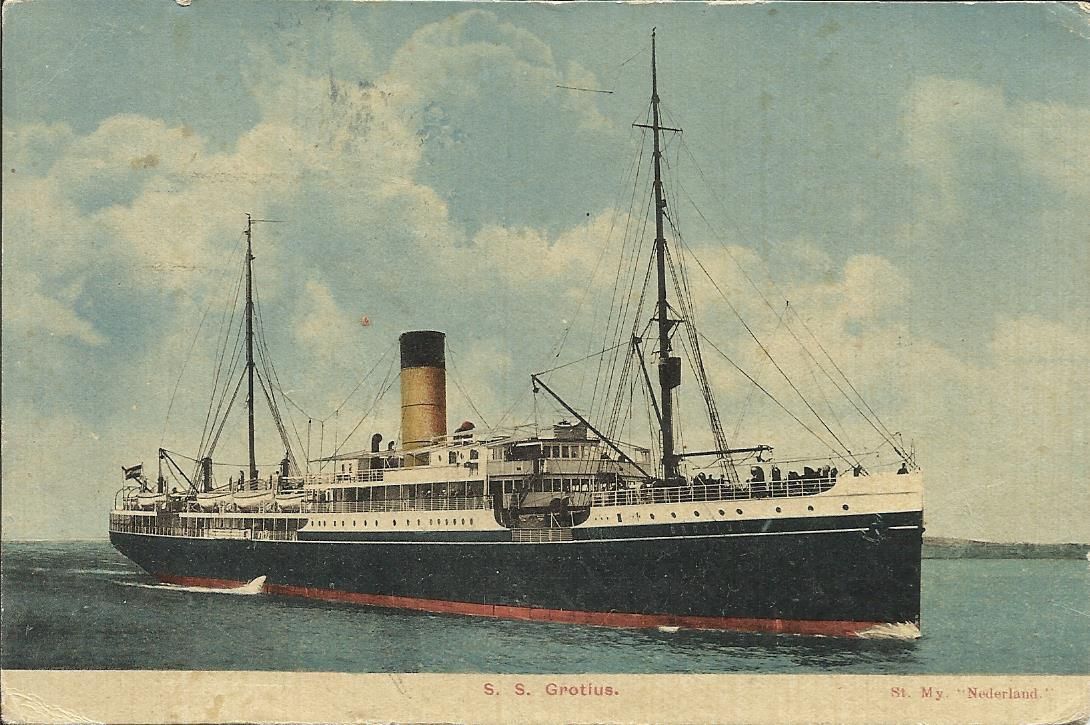

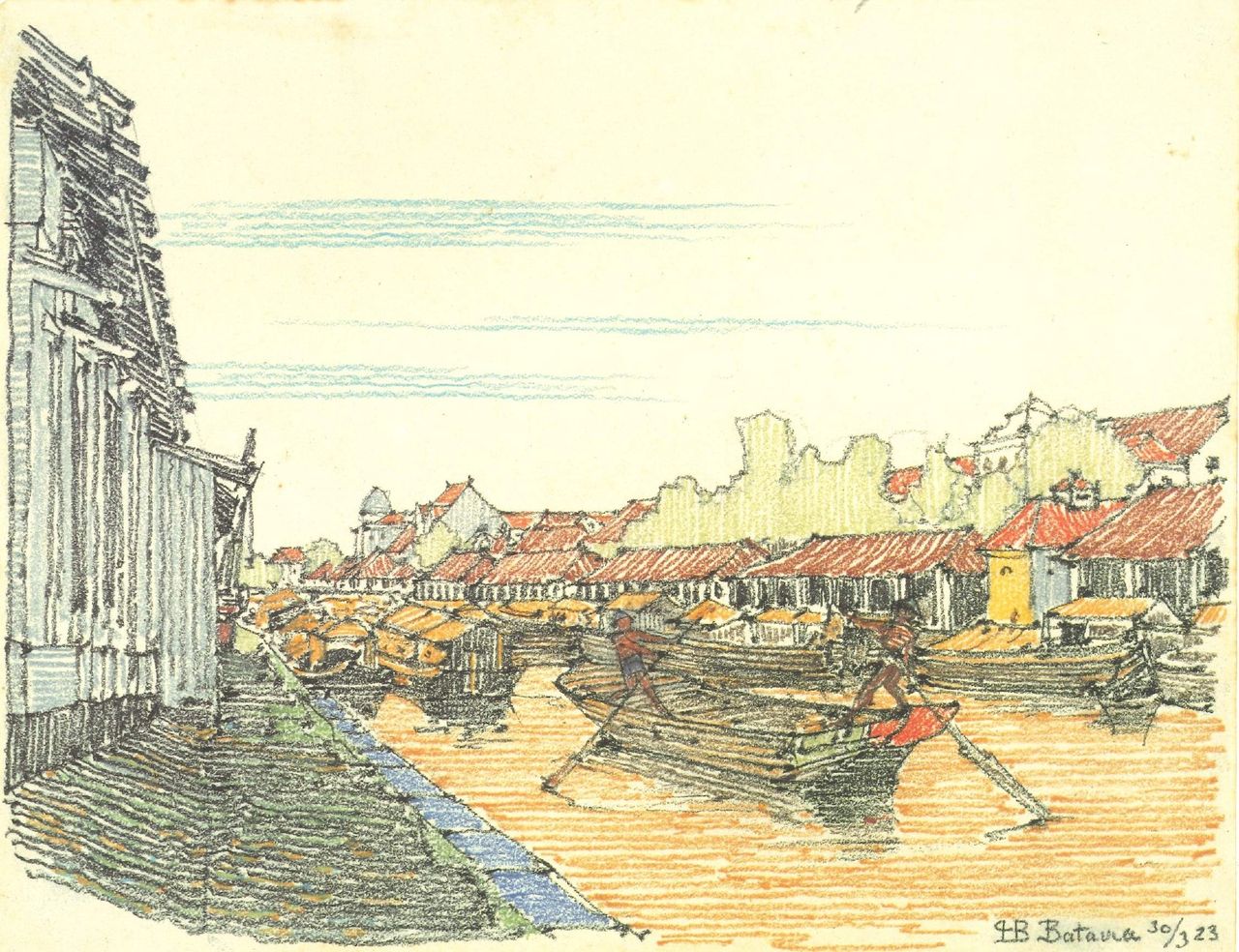

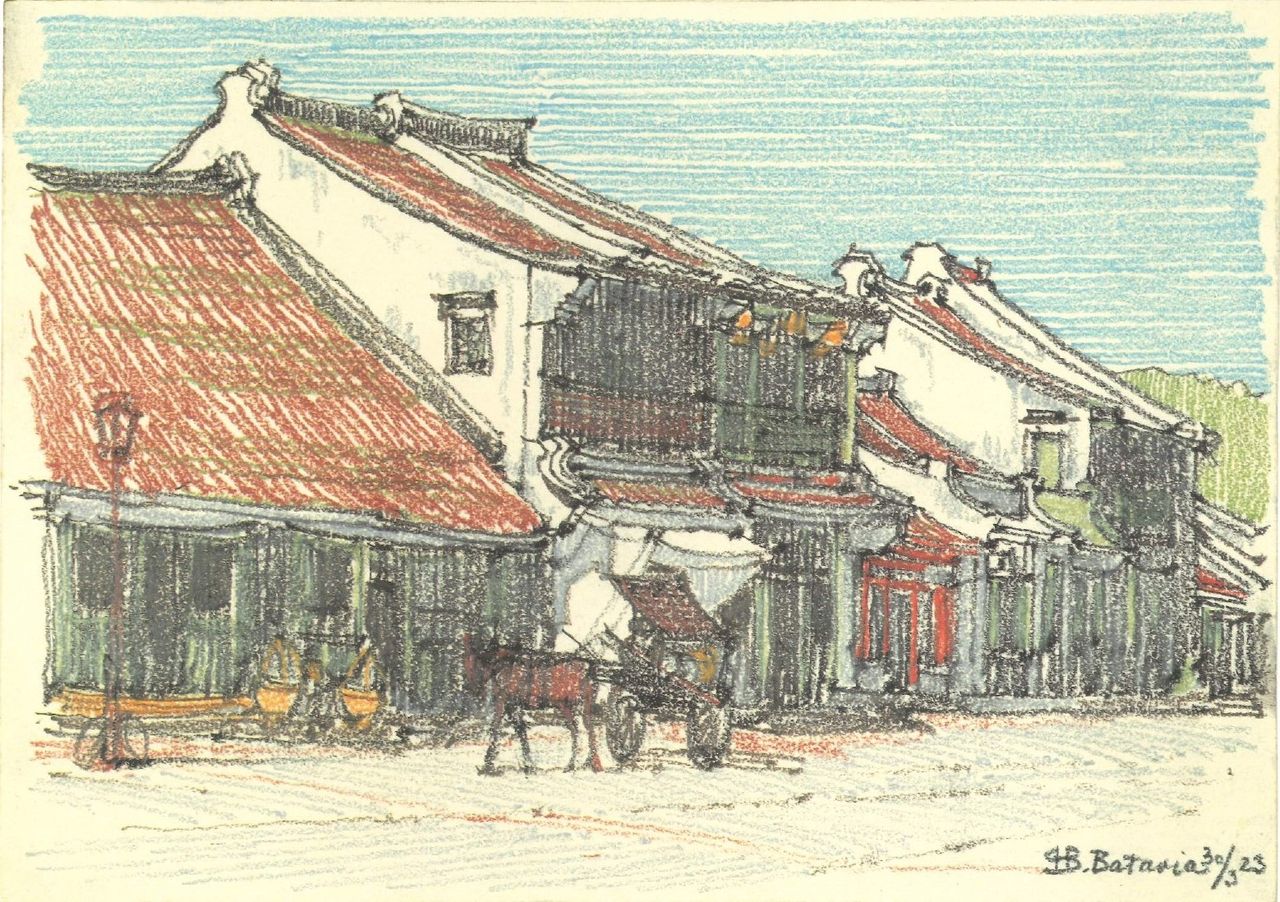

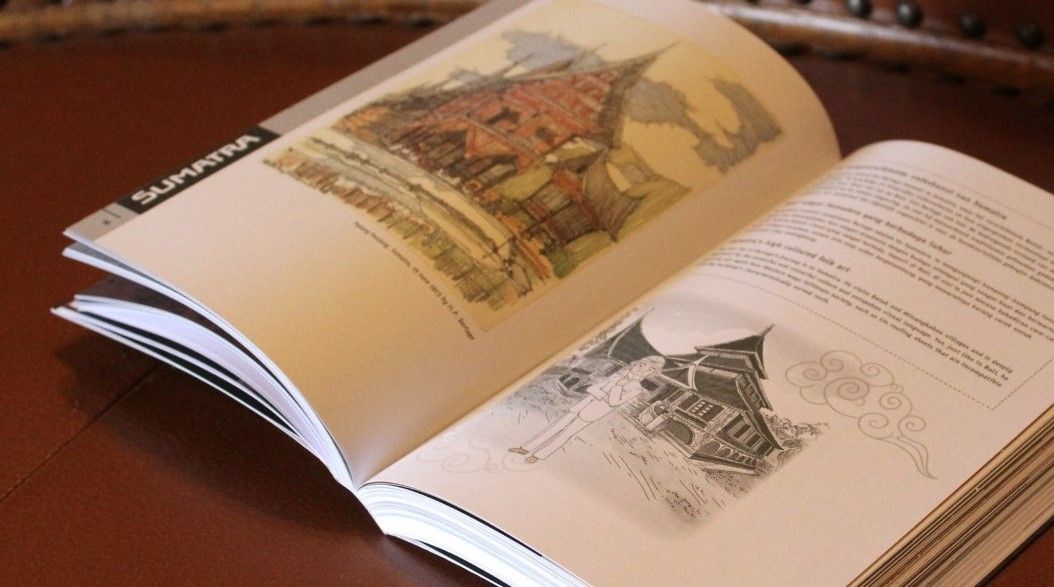

Perhaps more important than his physical legacy is Berlage’s contribution to the architectural discourse in the colony. In 1923, he spent three months travelling across Java, Bali and Sumatra. Berlage was at the pinnacle of his fame, and as a highly respected architect of his generation he was invited to deliver lectures in different cities. The colonial authorities had also asked him to advise them on the restoration of the Prambanan temple complex. This provided Berlage with the unique opportunity to crisscross the country and immerse himself into its ‘oriental culture’ that had fascinated him for so many years. For architects in the Dutch East Indies it was a chance to have a face-to-face encounter with the man who revolutionised architecture in their home country.

In the cold winter of 1923, Hendrik Petrus Berlage—'Hein' for friends— bought himself a new white tropical suit. He was preparing for a long journey to the Dutch East Indies, which is now Indonesia. For him it was the journey of a lifetime, a dream come true.

The streets, the houses, the ornaments, I feel like I could be walking anywhere in Amsterdam.

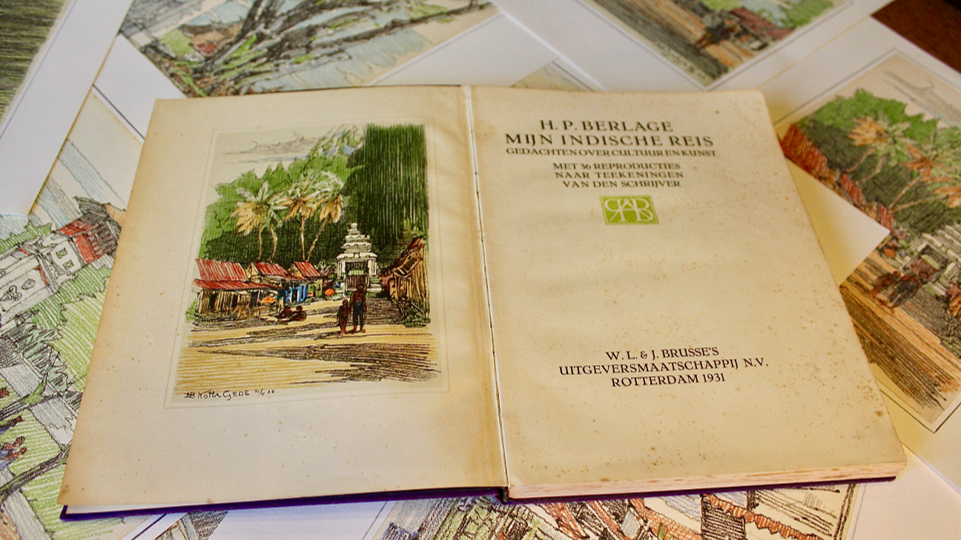

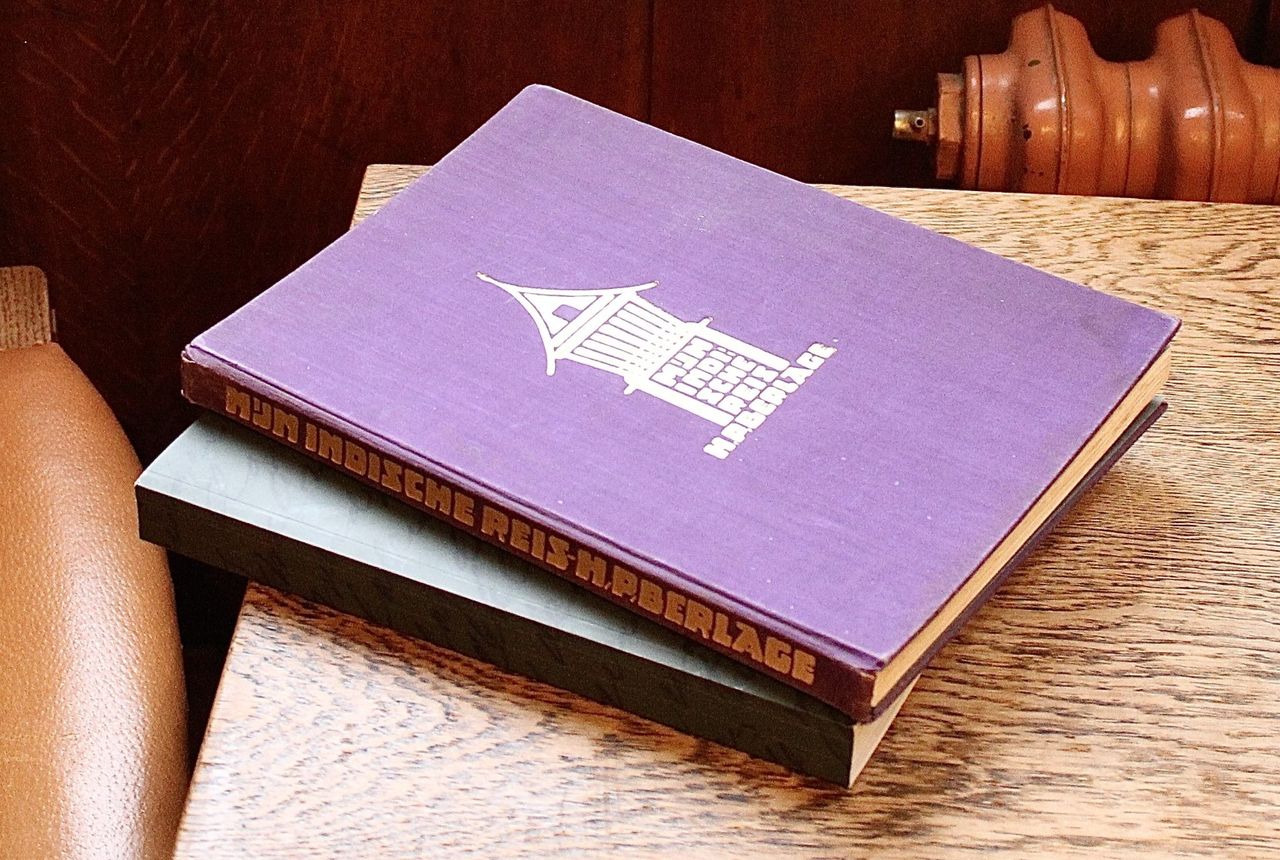

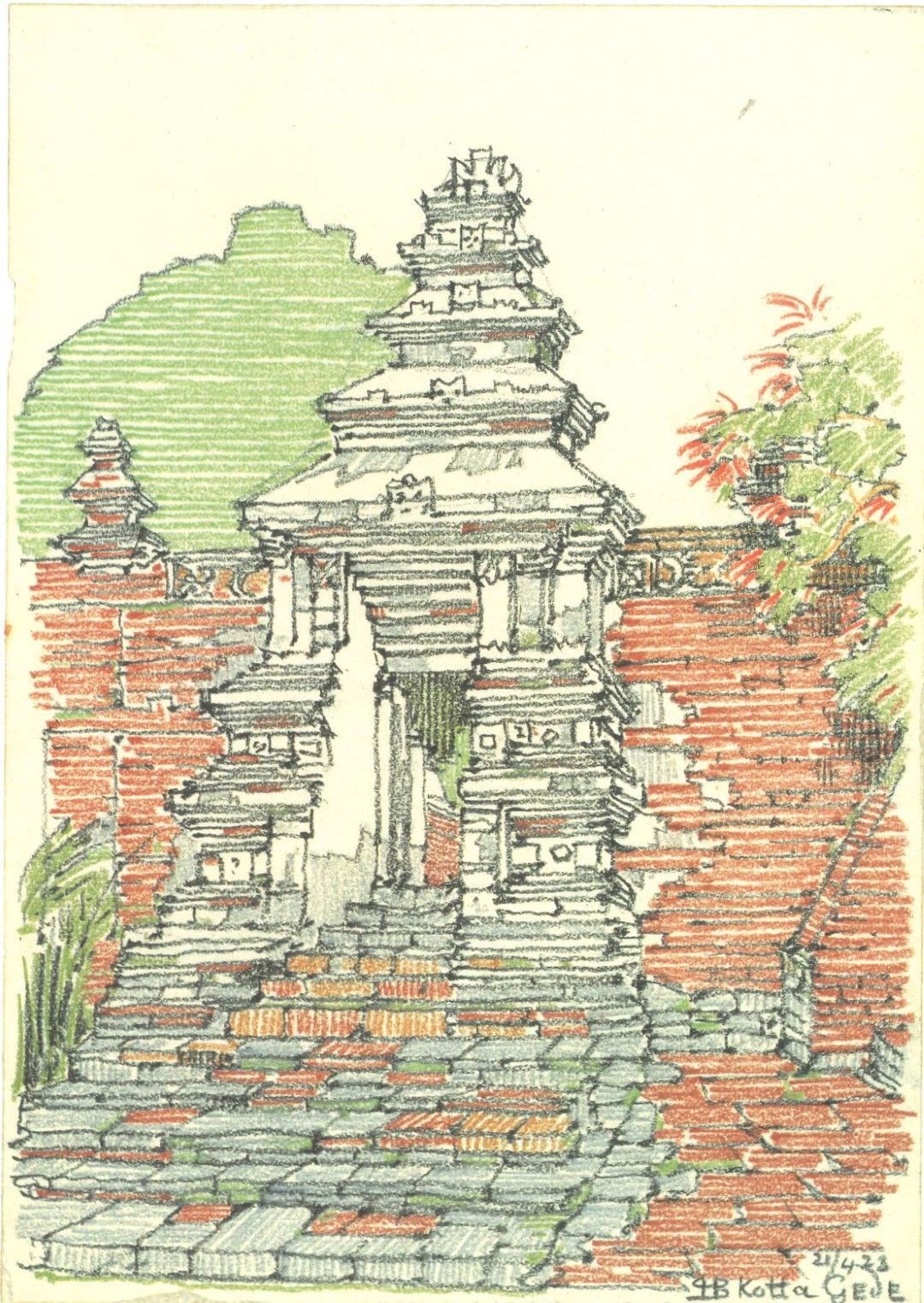

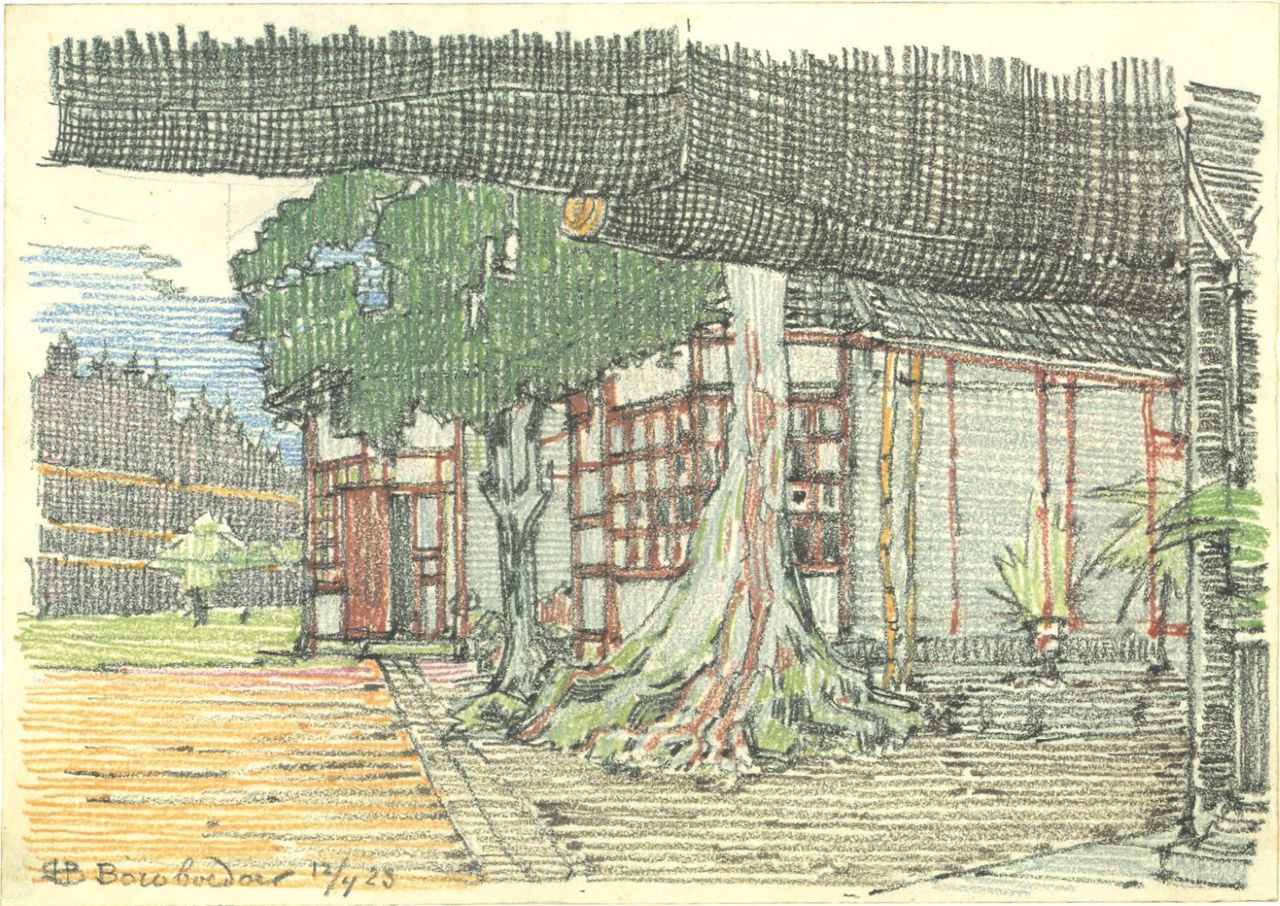

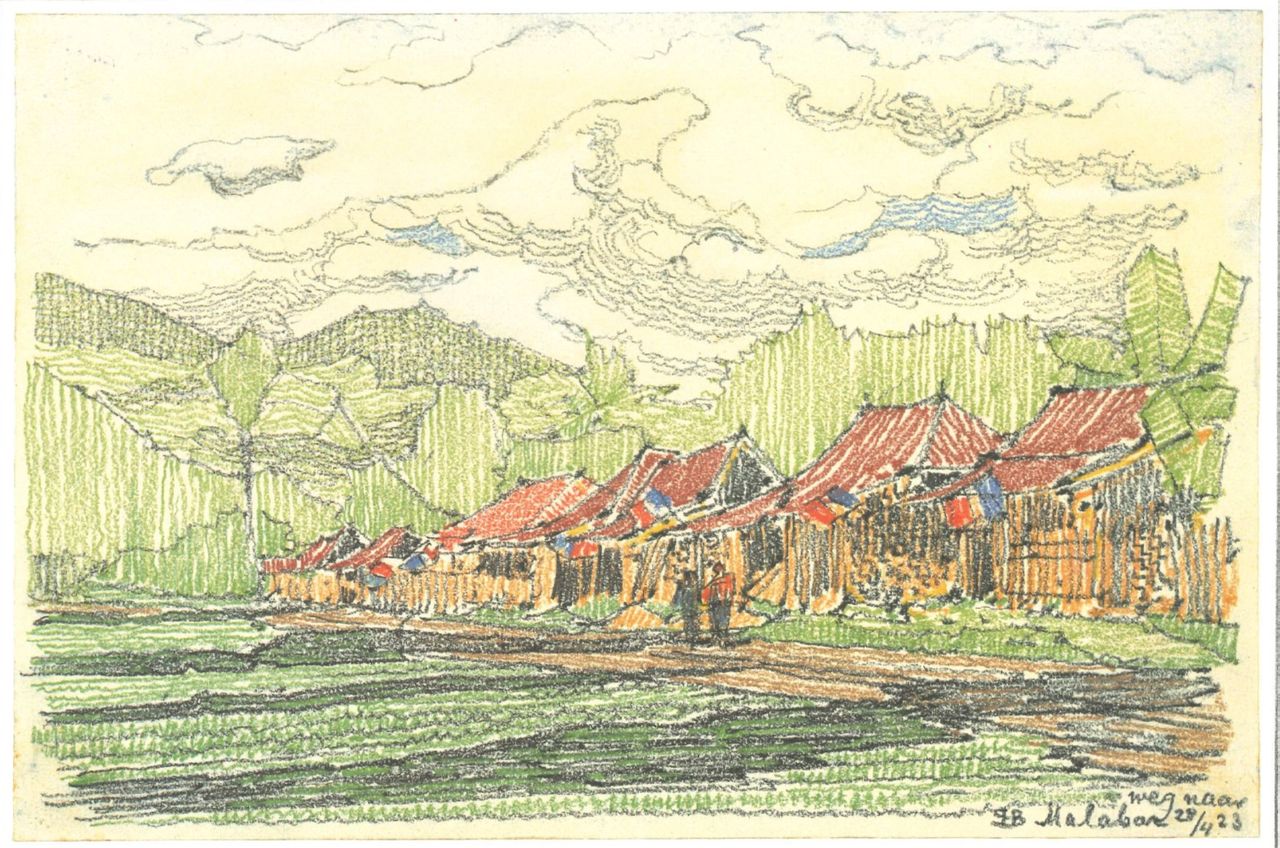

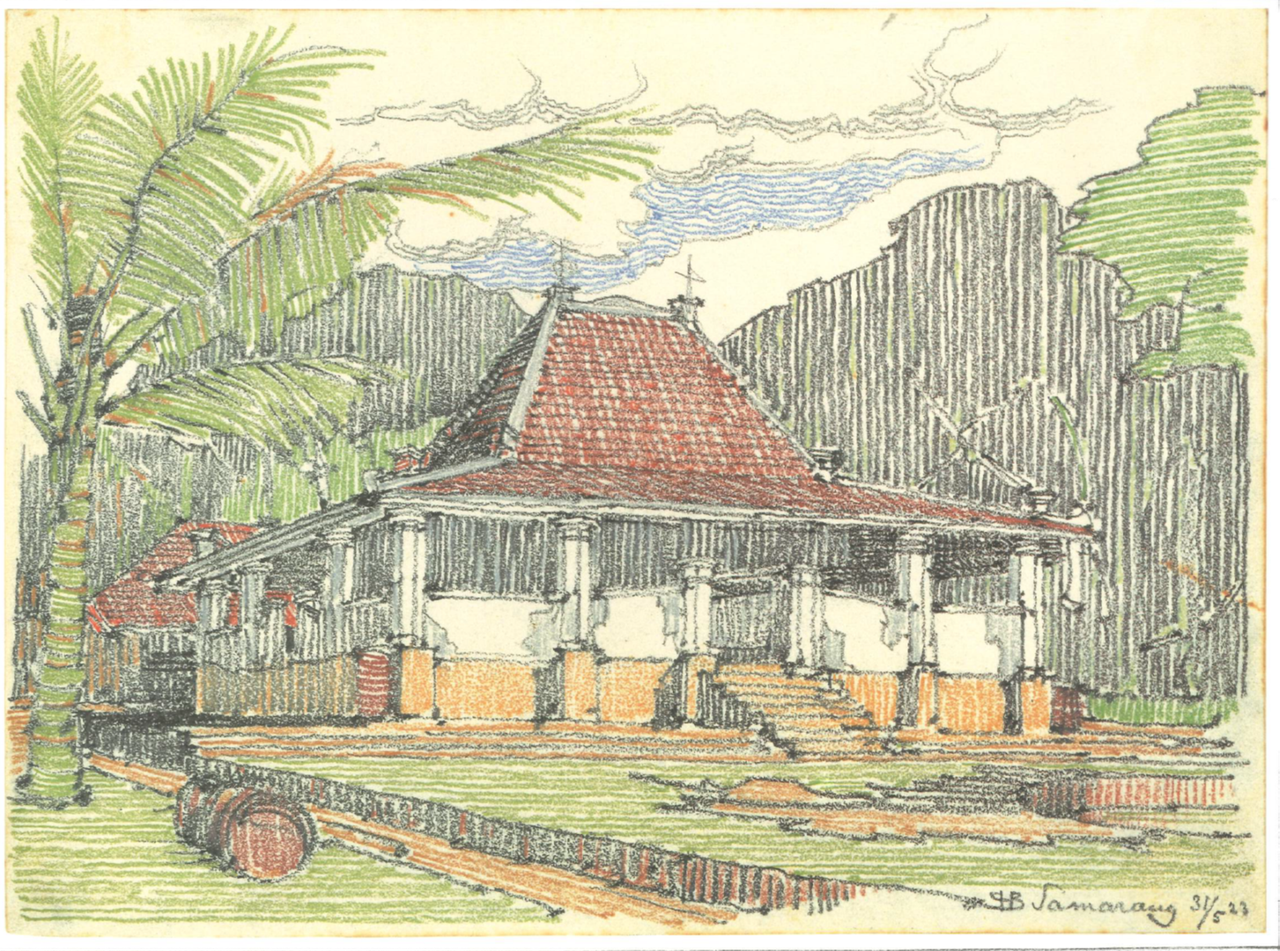

Berlage kept a travel journal, a meticulous record of his journey, filled with lyrical poems about Indonesian nature and culture, critical remarks on colonial architecture, and deep thoughts about the East and the West; a legacy beyond architecture and urbanism that was published eight years after his journey. Mijn Indische Reis (‘My Journey to the Indies’) is quite critical and very philosophical. As a committed socialist, Berlage found himself contemplating East and West, cultural identity and society. What deeply impressed him was the harmonious coexistence of culture and community and the spiritual appreciation for nature. He spent days roaming the ancient temple complexes of Java and Bali. The Dutch government had asked his advice of what to do with these decaying structures: to renovate or keep them as is. Berlage pondered this question and concluded that they should put measures in place to preserve the monuments, but avoid reconstruction at all costs. This was a subject of much controversy in those days, and Berlage’s opinion did not go down very well amongst the archeological community, many wondered why a Dutch modern architect had a say in this matter in the first place.

In Batavia, Berlage roamed the historic town of Kota Tua. The city took him by surprise: here he was, far away from home, and yet, his surroundings looked so familiar: “The streets, the houses, the ornaments, I feel like I could be walking anywhere in Amsterdam," he wrote in his journal. The colonial lifestyle did not impress him. "When you compare the gracefulness and sophistication of Javanese dance to the way the Europeans dance the foxtrot in the ballrooms of their societies […] a person can endure just about anything, but not such arrogant ugliness.”

These have turned out to be a complete failure. Every stylised lion's head [ kala kop ] above a doorway is a caricature.

“We land on Dutch soil, surprised so far from home to hear the language of Holland everywhere. This was the beginning, typical yet also poignant, of an ever-increasing astonishment at the possibility of governing such a vast empire from that little country ‘’perched between de Dollard and de Schelde’.”

Berlage felt uncomfortable in the colonial setting and was not afraid to discuss it. He was irritated by the behaviour of some Westerners he met, felt ‘foolish’ visiting the keraton in white tie and was generally appalled by the colonisers’ misguided sense of superiority. But what concerned him most was seeing how the indigenous culture crumbled from intrusion by western ‘civilisation’. As Berlage’s journey progressed, his conflicting emotions on colonial rule became increasingly apparent, undoubtedly aggravated by his meetings with like-minded individuals. Over the course of the three months, his attitude changed, slowly but surely, from wonder to astonishment and, finally, bewilderment.

As Berlage was known to be a socially driven architect who sympathised with communist ideas, it should not come as a surprise that he arrived at anti-colonial viewpoints. As a person of his stature and while in government service, he refrained from making bold statements on the Dutch colonial system, but between the lines, he certainly did drop hints of criticism. Upon his return to the Netherlands, in a private letter and a public lecture he rather unequivocally declared himself a proponent of an independent Indonesia.

I was amazed by the fact that a country so abundant in nature, bearing no resemblance whatsoever to the motherland, could belong to that same nation. For one wonders instinctively how it is possible that ‘they’ still concede us this possession.

What the West should learn from the East

More than any other of Berlage’s many publications, Mijn Indische Reis provided an insight into his personality. His Indies trip was much more than a physical voyage: it was a journey of the mind. Even now, the journal reads as a personal testimony to the artistic tradition and culture in the then-Dutch colony. As his journey progressed, Berlage became more and more taken by the collective spirit of the local community. He contemplated how Indonesian people live in harmony with nature, a stark contrast to the increasingly individualistic Western society. The more he saw, the more he described the East and West as opposing characters and how “the Western influence is threatening to rob the Orient of this quality.”

What typifies the bustle of the Orient is the silence, in the bustle of the West it is the noise. The Orient still knows style as the natural quality of all things, art as an expression of culture. The West has long lost that.”

For many years, Berlage had been searching for his ideal society. In Bali, he finally found it: a society in which the natural tripartite human, religion and culture takes centre stage, where the collective interest overrides individual desires and collectively created forms of art represent the soul of the community. In his travel journal he advocated for a less judgemental attitude to life and concludes with the rhetorical question “would not a little more modesty befit the Westerner?”. Instead of assuming that the East could learn a thing or two from the West, Berlage turned the narrative around: he searched for what people in the West could and should learn from the East.

The becoming of an Indo-European architecture

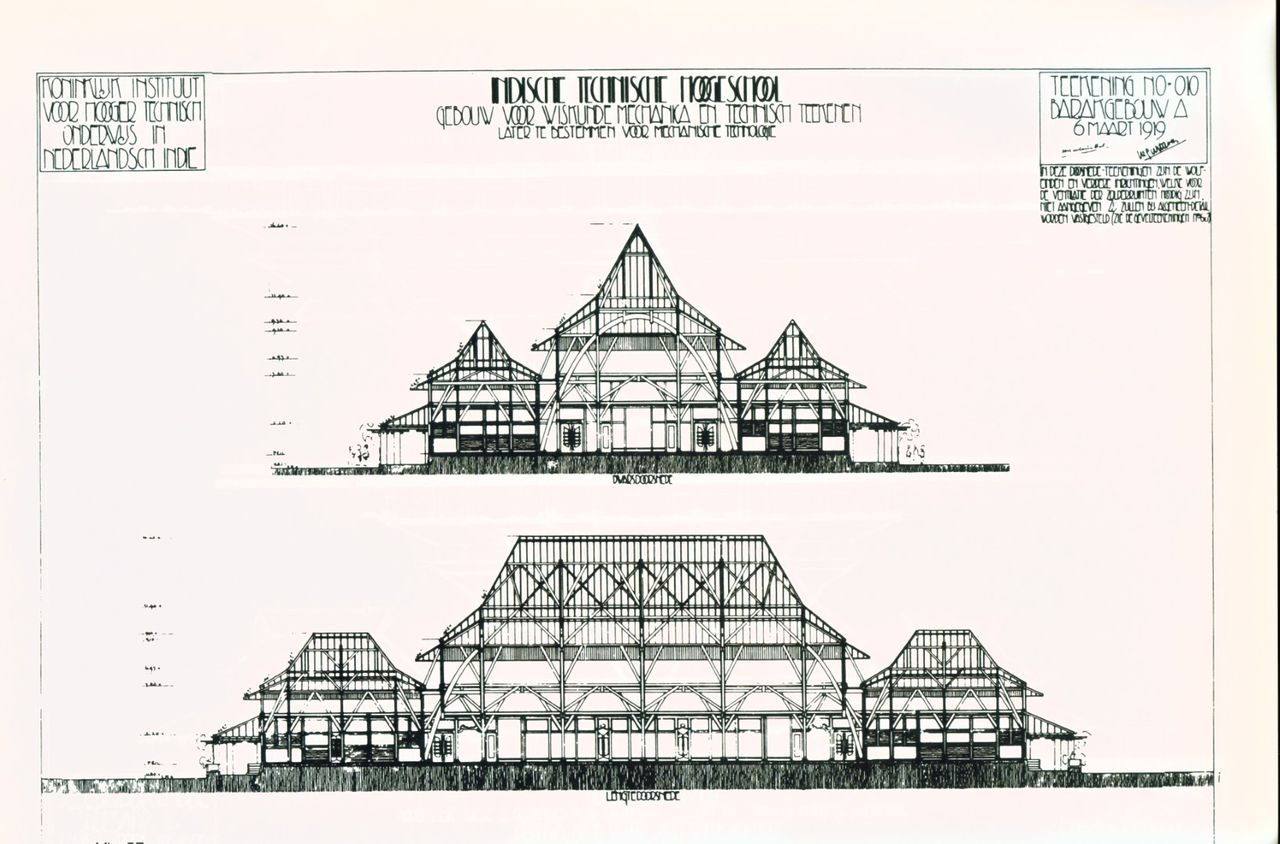

As could be expected from an architectural innovator, Berlage was quite critical of the works of his fellow Dutch colonial architects. He disliked neoclassical buildings and had nothing positive to say about the random use of Javanese-inspired ornaments, the pages dripping with criticism. He described the works of celebrated architects as cold, distant and tenuous in dead European (Greek, Gothic Renaissance) styles. He did rather like the ideas of young Indonesian architects and was unequivocal in his admiration of the work of Thomas Karsten, Henri Maclaine Pont and Pieter Moojen, the pioneers of het ‘Indische Bouwen’ (Indo-European architecture). These architects and city planners were moving away from Dutch design. Instead, they merged Western and local architectural styles, choosing construction elements that suited the tropical climate and local culture and used indigenous building materials and furniture. In Mijn Indische Reis, Berlage advocates for the development of a true Indo-European architecture based on the indigenous archetypal structure of the pendopo, a large open-air pavilion built on columns.

They may not know it here, but we'll tell them what I saw there, that will open their eyes.

Even after returning home, Berlage tried to remain involved in the architectural debate in the colony. We know that directly after his trip, in the summer of 1923, he attended an architecture exhibition in Amsterdam and told fellow architects about the ‘emerging talents’ and the ‘development of an Indonesian architecture that was just as important as the development of modern Dutch architecture’. In his lecture, he even explicitly mentioned Indonesian architects by name: Notodiningrat, the first Indonesian civil engineer who graduated from Technische Hoogeschool Delft and worked at Lands Openbare Werken, and Soerjo Winoto, a Javanese prince who was among the first generation of Indonesian students in the Netherlands. In the same lecture, rather unexpectedly, Berlage used the term ‘Indonesian architecture’ instead of ‘Indies architecture’, the latter being the common term at that time.

We also know that together with Thomas Karsten, Berlage instigated a research study into Balinese art, culture and architecture, but due to the recession, those plans never materialised. Finally, Berlage also proactively advocated for establishing an architectural school with local faculty for local students at the Technische Hoogeschool in Bandung (now Institut Teknologi Bandung). For him, this was a crucial precondition for the further development of Indo-European architecture. Berlage even wrote letters to the Hoogeschool’s first Vice-Chancellor Jan Klopper as a gentle reminder of the importance of this matter. In one of his letters, he states that “[...] a true Indo-European style will only develop when the nation gains its independence, with which I fundamentally agree.”

What remains a mystery is why Berlage did not mention the two office buildings he designed in his travel journal: not one word among the 147 pages. One wonders what he thought when he saw his creations, because he must have seen them. As a visionary architect, perhaps he scrutinised his own designs with the same lens he critiqued his peers in Mijn Indische Reis. After all, his two buildings exemplified European building design with little reference to the local context. It would have been interesting to see what he would have come up with had he been commissioned to design a new office building after his journey…

A true Indo-European style will only develop when the nation gains its independence, with which I fundamentally agree.

The impact of the journey on Berlage’s design philosophy

Has Berlage’s experience in the East influenced his later designs at all?. Some say that his works post-1923 carry influences of the Indies, like the ‘abstract ornamentation’ and ‘meandering lines’ in his design for the head office of the Nederlanden van 1845 in Den Haag (1925). Others point out that the layout of Berlage's masterpiece, the Den Haag Art Museum, has been inspired by Hindu-Javanese temple design. The museum features a long corridor to mark the transition from the real world into a 'palace of the arts', which art dealer and Art Nouveau/Art Deco expert Frans Leidelmeijer describes as: “a rite of passage to empty the mind before surrendering to the art”.

Berlage’s design journey for Den Haag’s new museum indeed intertwined with his trip to the Indies. The first ‘megalomaniac’ design dated back to 1920 but was rejected by the Municipal Council. What followed was a period of back and forth and Berlage must have received the definite no-go just around the time of his journey to the Indies. Only years later, in 1927, he was commissioned to submit a revised, less ambitious version of his ‘dreamed museum’. Construction commenced in 1931, but Berlage never got to see his design come to life: the master architect passed away in 1934, a year before the museum was completed.

Yet, there is no profound visible impact on Berlage’s subsequent work. Unlike the Amsterdamse School architects, who found inspiration in the exotic brick ornamentation in the Indies and implemented them into their designs in the Netherlands. It seems like Berlage's Indies trip struck more of a cord with the social commentator than the architectural designer in him.

They may not know it here, but we'll tell them what I saw and that will open their eyes.

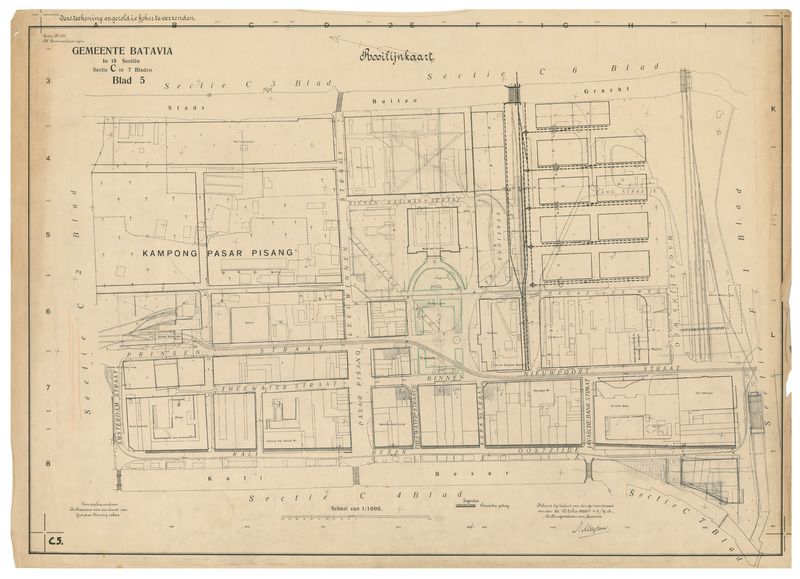

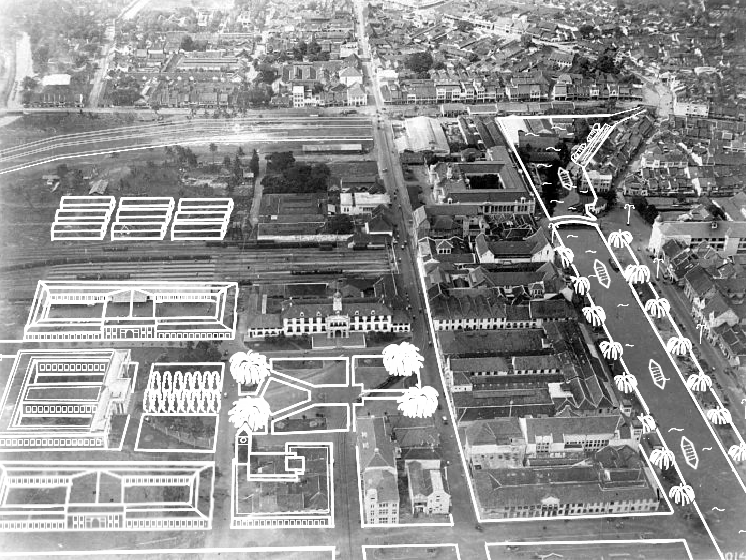

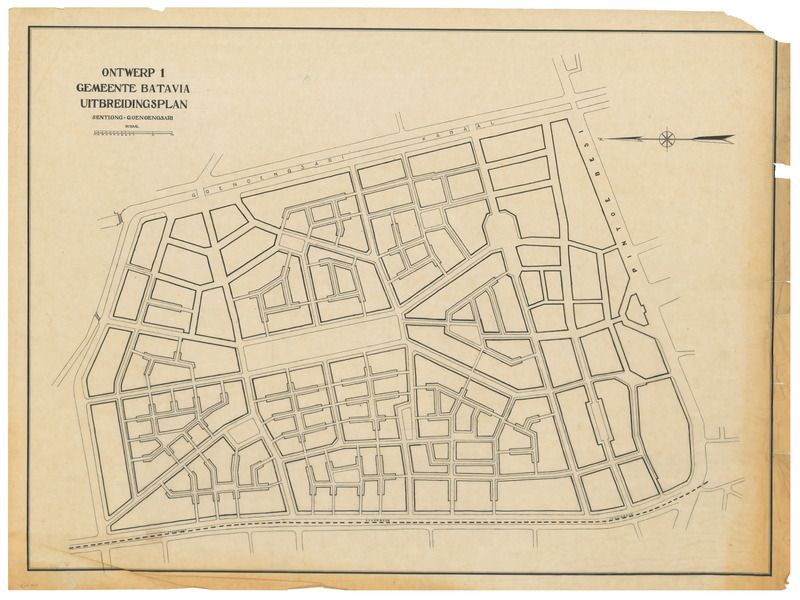

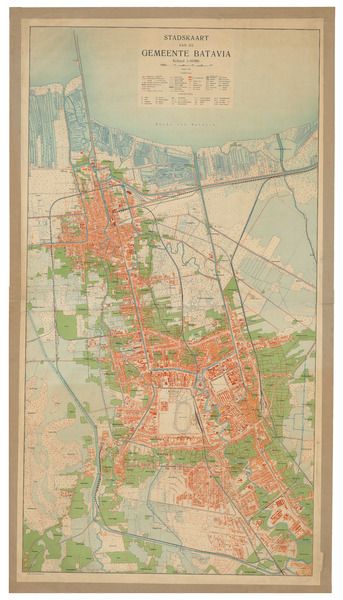

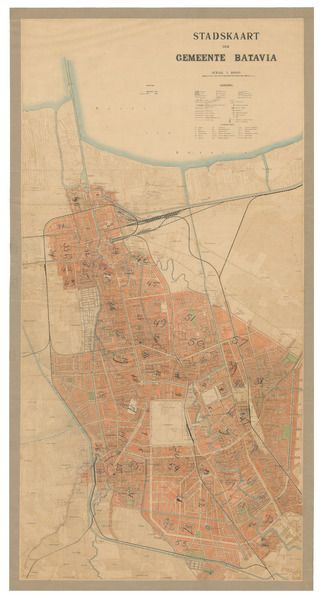

Berlage's Batavia

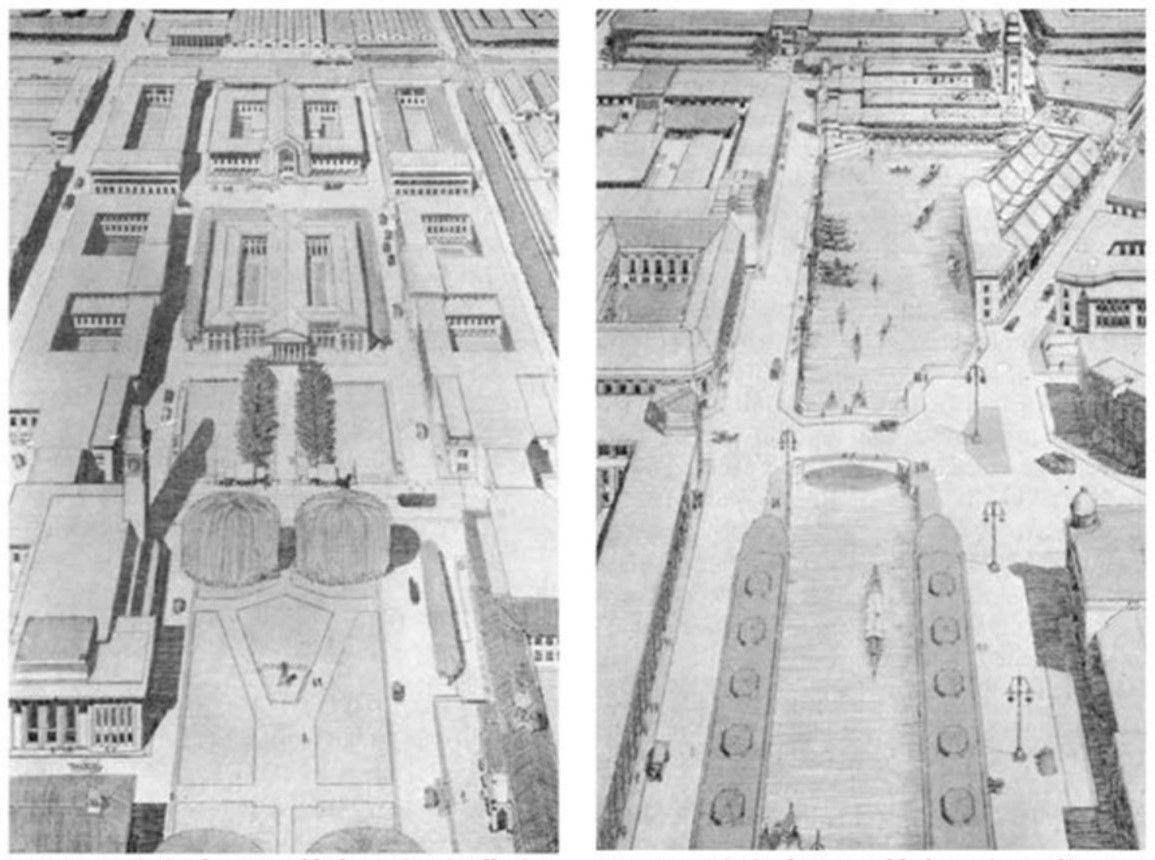

Finally, there is one more destination where one can try to find clues to Berlage's Indonesian legacy: his urban plans for the city of Batavia. During his trip, Berlage lectured at the Batavia Kunstkring, in which he shared some observations about the future development of the city. A clever move, as the city council promptly asked him to to advise them on the extension plans for the new part of Batavia and redesign the old colonial city centre (now Kota Tua). His plan for Amsterdam Zuid in 1917 had established Berlage’s reputation as a visionary urban planner, while the thinking about comprehensive city planning in the Dutch East Indies had only just started to emerge.

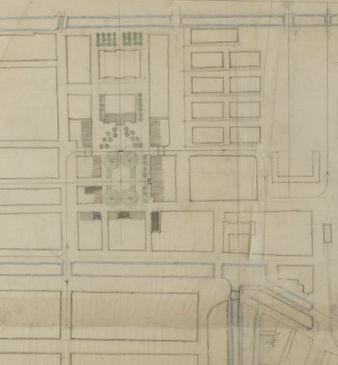

Stadhuisplein

For the ‘Stadhuisplein’ – as it was called in those days – Berlage took inspiration from old Javanese principles of city planning whereby the central square (alun-alun) is typically adorned with large sacred Waringin trees. He suggested putting four of these monumental trees at either side of the square and a line of smaller trees from the Palace of Justice leading to the square. Along the Kali Besar (‘The Grand River’) he foresaw a line of trees, and he planned an inner harbour to the back of the newly built head office of the Javasche Bank.

Yet, Berlage's ideas did not go down very well in the press. Furthermore, the fees he requested were too steep, even for the colony’s coffers, and so, his plans were never implemented. In his book Planning the Megacity: Jakarta in the Twentieth Century, Christopher Silver says: "While devoid of the aesthetic splendour of Berlage’s plan, the more unified conception exceeded expectations and perhaps available resources of the Batavia leadership".

If the city plan is continually modified, as long as this is managed well and executed by architects imbued with an understanding of an Indo-European style, a future Batavia at its most beautiful awaits us.

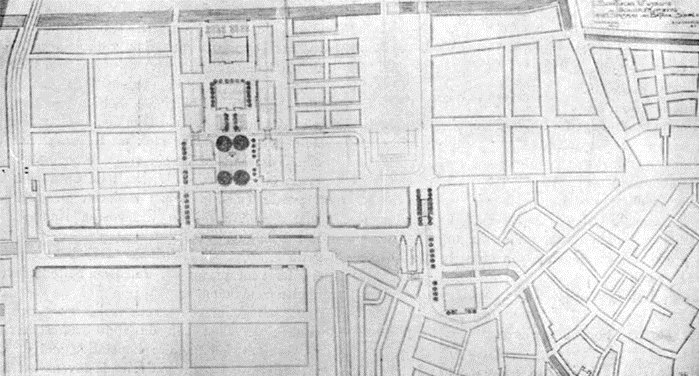

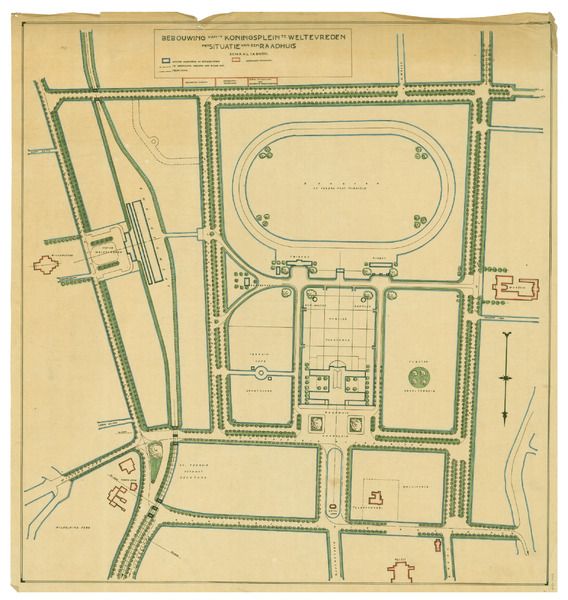

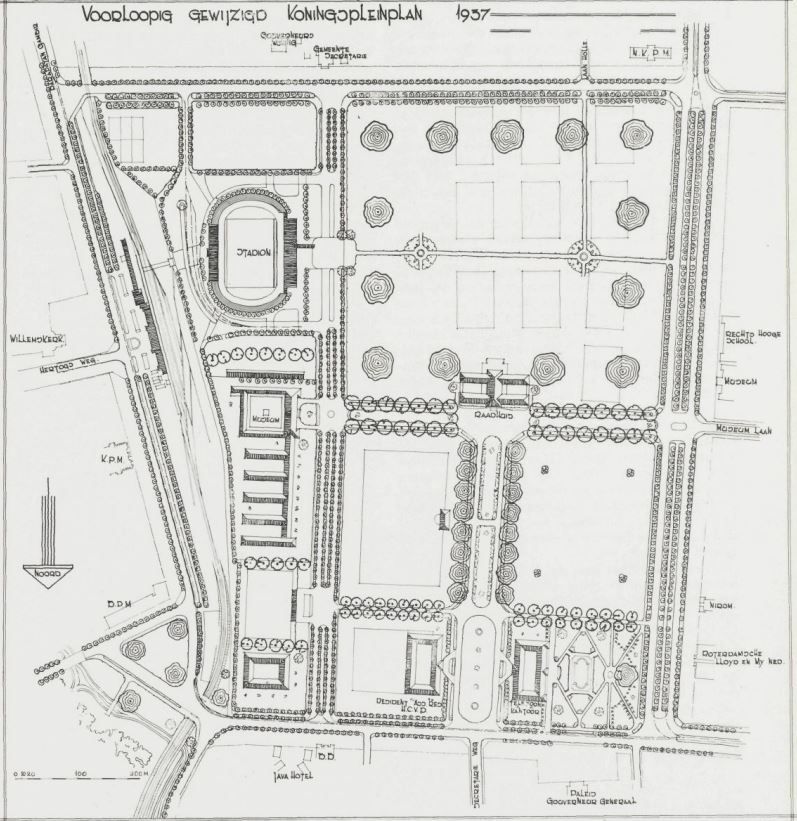

Koningsplein

Berlage was also asked to review the plan for the new Koningsplein, now Medan Merdeka. In those days, it was a wide, open field; Berlage even referred to the square in one of his lectures as ‘ignored, messy, with random structures,’ and even refused to call it a square in the first place. At the time of Berlage’s visit, his contemporary Thomas Karsten—the man responsible for urban expansion plans in many Indonesian cities—was working on redesigning the square, and what he proposed was a manifestation of a new approach to city planning. Karsten placed the town hall in the centre, amongst open green squares at the junction of two tree-lined boulevards and included intricate gardens. Berlage reviewed Karsten’s design for the beautified public space as ‘splendid’, and eventually, in 1937, his plan was adopted by the city council in favour of other proposals by a.o. Fermont-Cuypers.

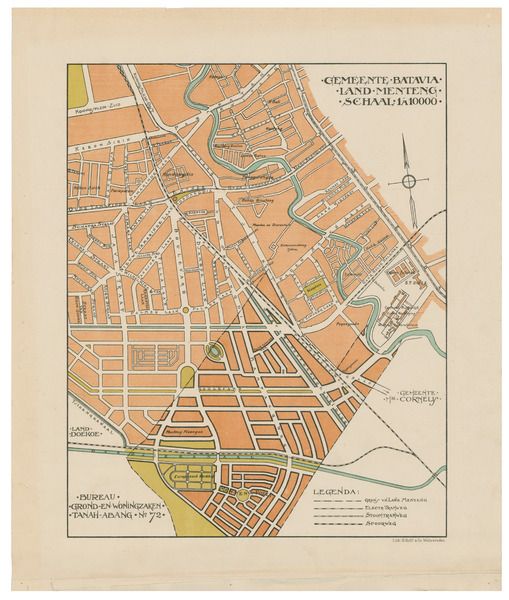

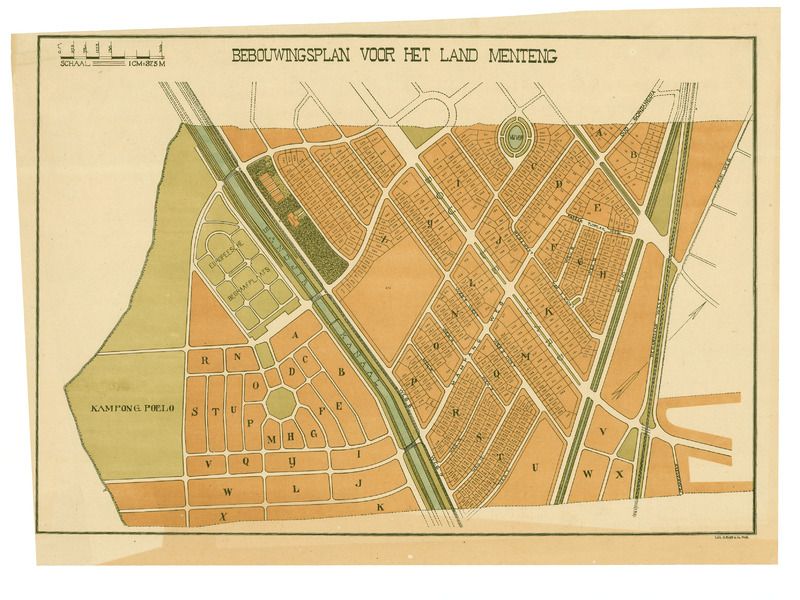

Menteng

In Batavia, the city authorities began planning for an extension of the city in 1910. At the time, Weltevreden, the city centre, was already very crowded while new immigrants kept arriving. So, the Batavia City Council set out to create a new residential district to accommodate the growing population of middle-class Dutch Indonesians. The choice fell to the southern part of the city, where they acquired more than 500 hectares of paddy fields and ponds to create a new modern tropical garden city: Menteng-Nieuw Gondangdia. The City Council appointed architect Pieter A.J. Moojen as chief planner of the Menteng master plan. Moojen was the first independent architect in the Dutch East Indies who worked in a truly contemporary architectural style and had built up a reputation as a pioneer of modern tropical building.

Like much of Berlage's work, Moojen's designs were characterised by a rationalist approach. His plan for Menteng, inspired by Ebenezer Howard’s idea of a garden city, combined wide, cross-cutting boulevards with concentric rings of streets and a central public square. At strategic locations, Moojen planned iconic landmarks such as the Bataviasche Kunstkring (now known as the Kunstkring Art Gallery). Menteng was to become a lush district with about twenty public gardens and dedicated green spaces at each street corner. Public facilities, such as the church, school and public offices, were accessible by public transportation such as trams and horse carts. Moojen's plan was later amended by F.J. Kubatz and by the time Berlage was visiting, construction was well on its way. He liked what he saw: "I feel as if in Baarn or Hilversum,"

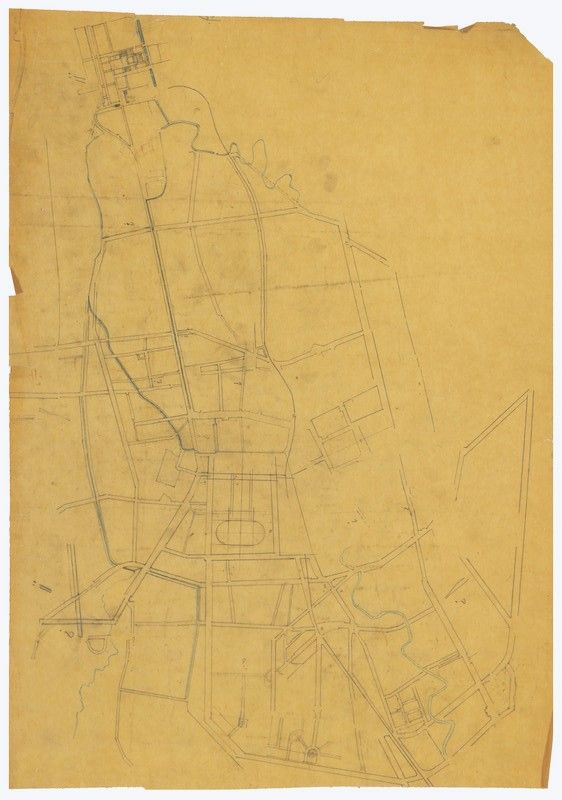

Actually, layout plans and street patterns for residential neighbourhoods in Menteng show up in Berlage’s archives at the Nieuwe Instituut. It is unsure whether the architect actually worked on these plans or whether they were sent to him for his commentary. Whichever way, whether in spirit or in the stroke of his pencil, Berlage’s urban planning philosophy—which later also manifested in his vision for Amsterdam South—is also present in the layout of one of the most progressively planned neighbourhoods in the Indonesian capital.

If the city plan is continually modified, managed well and executed by architects imbued with an understanding of an Indo-European style, a future Batavia at its most beautiful awaits us.

A future for the past?

How can Berlage's legacy help to navigate a future path for the dilapidating Gedung Singa in Surabaya? The heritage building is owned by PT Jiwasraya/IG Live. In 2021, Berlage’s building was put up for public auction; the first round had no successful bids. In 2024, as part of a ‘revitalisation’ effort, BPBD task force (disaster prevention) officers painted the building white, even the original exposed red brickwork and the stone lions did not escape the paintbrush. This led to a public outcry led by local heritage NGO Begandring Soerabaia and the paint job was promptly abandoned.

With help from heritage experts from the Netherlands, Begandring was able to pull out the original drawings of the building to undo the damage. They also continue to campaign and liaise with local government, MPs and commercial parties to explore options to buy or leaseback the building. Their goal is to repurpose Gedung Singa, keep it accessible to the public and include community use such as education, research, culture or tourism.

We are here everyday and not allowed to damage cultural heritage buildings. We comply with that. But instead, this revitalisation has actually damaged part of the building.”

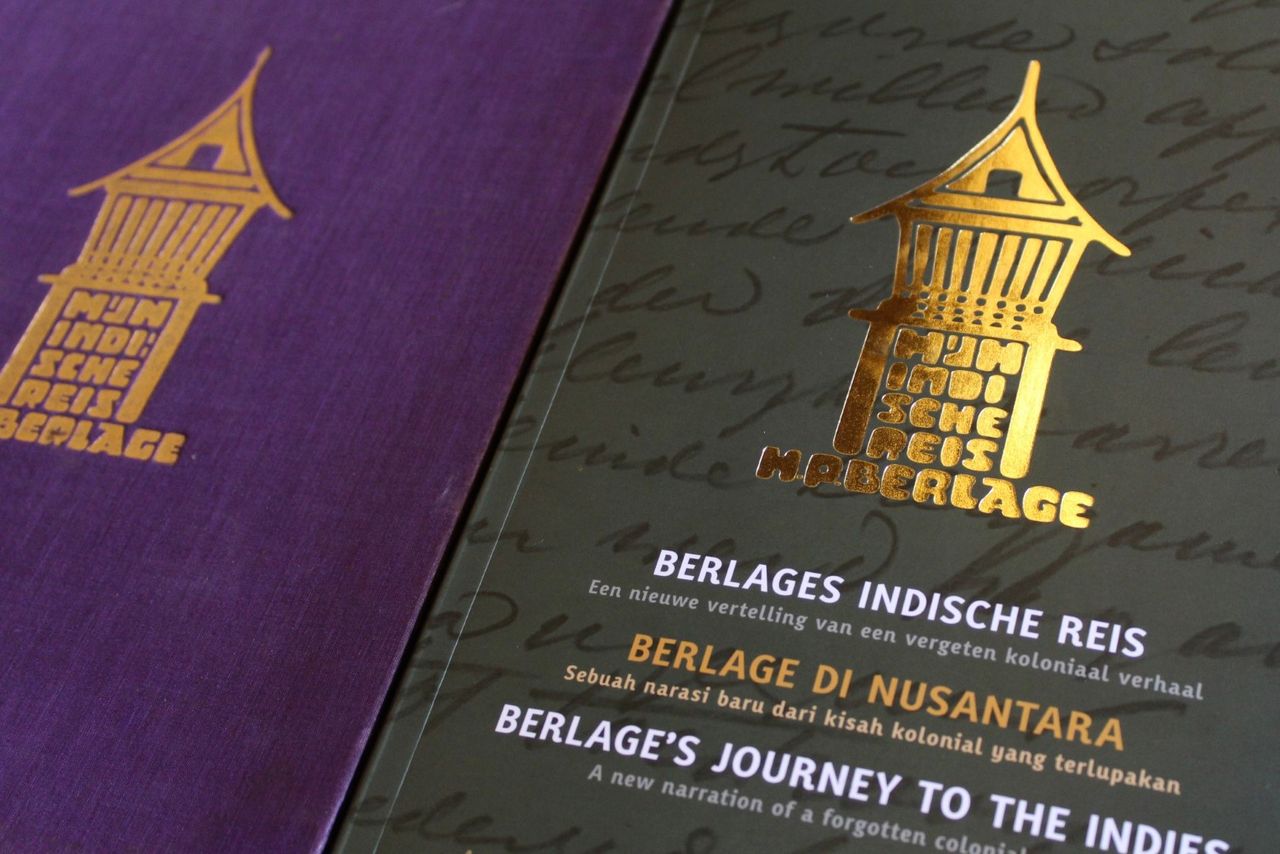

Their crusade is strengthened by the growing interest in (colonial) history and heritage in Indonesia and the Netherlands, especially among the so-called ‘third generation’. The new translation of Berlage’s travel journal into Indonesian and English also provides an opportunity to explore ‘the other side’ of Berlage’s Indonesian heritage: not just his physical legacy, but the imprint of his design philosophy on the course of architecture and city planning in the archipelago as well as his erudite anthology of art, culture and local wisdom in Indonesia.

Berlage’s journal also triggers the examination of cross-pollination; little is known about whether his philosophical observations and social commentary found resonance in the Netherlands back in the 1930s. But, even a hundred years later, his observations are again – or still – incredibly relevant. Quotes from Mijn Indische Reis can serve as starting points to discuss contemporary topics such as cultural identity, diversity, sustainability, and decolonisation. A spotlight on Berlage's journey could also bring a fresh perspective to rediscover and critically address this puzzle piece of the Dutch-Indonesian shared cultural heritage and challenge the current discourse on colonial history.

The community can play an active role if they know more about the Old (European) City of Surabaya. Don’t let them continue to be just spectators of this process.

Explore more

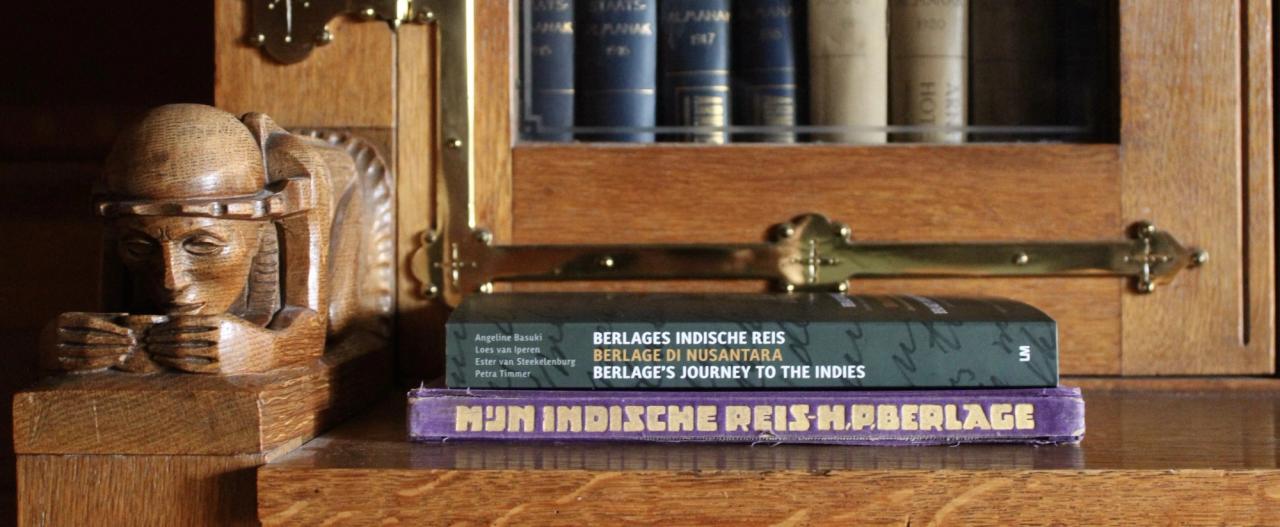

Berlage's journal Mijn Indische Reis; Gedachten over Cultuur en Kunst was published in the Netherlands by W.L. & J. Brusse in 1931. In 2023, a century after Berlage’s journey, a creative reinterpretation of his original journal was published by LM Publishers in July 2024. Titled Berlage’s Journey to the Indies (Indonesian title: Berlage di Nusantara, Dutch title: Berlages Indische Reis), this trilingual book is an abridged version where Berlage's most interesting quotes, thought-provoking passages and his most beautiful sketches take centre stage. The book also features old photographs and prints, new illustrations, and provides historical context to and commentary on his trip to continue Berlage's legacy. And so, his journey continues a century later.

Find Berlage’s two buildings in Indonesia:

- Jakarta - The office building of De Nederlanden van 1845 (predecessor of Nationale Nederlanden) (1913) Jl. Pintu Besar Utara No.4, Jakarta 6°08'10.3"S 106°48'48.6"E

- Surabaya - The office building of the Algemeene Maatschappij van Levensverzekering en Lijfrente (1900). The property was taken over by Amstleven, which after a series of mergers and takeovers also became part of Nationale Nederlanden. Jl. Jembatan Merah No.15, Surabaya. 7°14'13.6"S 112°44'15.9"E

Surabaya Kota Lama walking trail

Walk around Surabaya's old city centre and discover the story behind Berlage's building and more hidden heritage gems with iDiscover Kampung Eropa Map, created by Begandring and Surabaya Memory and designed by Celcea Tifani. Available as a free download here ->

About the authors

This article is a spin-off of the research for the book BerlagediNusantara by an international editorial team: Dr. Petra Timmer (Editor-in-Chief, Historical Research), Dr. Ester van Steekelenburg (Initiator, Editor & Creative Concept) Angeline Basuki (Editor, Translator & Social Media: Moderation) and Loes van Iperen (Editor & Social Media: Content Creation & Design).

This article was written by:

Dr. Ester van Steekelenburg

Is one of the co-founders of Urban Discovery, a creative agency that works on heritage revitalisation and interpretation projects for clients like the Asian Development Bank, UNESCO and international cultural agencies. Ester is the initiator of the BerlagediNusantara project and also the brains behind iDiscoverMaps, a digital platform where residents can map what matters in historic neighbourhood and curate their own walking trails.

Find Ester on @LinkedIn

Nanang Purwono

Nanang Purwono is one of the founders of Begandring Soerabaja, an NGO that initiates projects to better protect and understand the heritage in the city of Surabaya. As a former journalist, Nanang tirelessly publishes articles and books to fight for the preservation of Gedung Singa and educate the public in and around Surabaya on the city’s hidden (hi)stories, like the city's European cemetery and Berlage’s relationship with Thomas Karsten.

Find Nanang at @Begandring Soerabaia

Dr. Petra Timmer

Petra Timmer is an art and architecture historian and works as an independent curator, researcher, author and lecturer for cultural institutions and leading museums, particularly in The Netherlands and Indonesia. Petra is one of the founders of TiMe Amsterdam (Timmer & Meijer) international heritage consultants and she is also currently a fellow at Utrecht University, to continue her research into Berlage’s journey in the Dutch East Indies. Petra spends her time between Indonesia and the Netherlands.

Find Petra on @LinkedIn

Sources

- Akihary, Huib (1990): Architectuur & stedebouw in Indonesië 1870 / 1970, Zutphen, De Walburg Pers

- van Bergeijk, Herman, (2011) Berlage en Nederlands Indië, een Innerlijke Drang naar het Schoone Land, Rotterdam, Uitgeverij 010

- Coté, Joost, O’Neill, Hugh (2017), The Life and Work of Thomas Karsten, Amsterdam, Architectura & Natura Publishers

- Heuken, Adolf, Pamungkas, Grace (2001) Menteng: The History of the First Garden City in Indonesia

- Norbruis, Obbe (2018): Alweer een sieraad voor de stad: het werk van Ed. Cuypers en Hulswit - Fermont in Nederlands Indië 1897 - 1927, Volendam, LM Publishers

- Passchier, Cor (2016): Bouwen in Indonesië, 1600-1960, Volendam, LM Publishers

- van Roosmalen, Pauline K.M. (2008): Ontwerpen aan de stad Stedenbouw in Nederlands-Indië en Indonesië (1905-1950)

- van Roosmalen, Pauline K.M. (2007), Familiar, Yet Different, Indische Architecture and Town Planning, Groniek Historisch Tijdschrift 174

- van Roosmalen, Pauline K.M. (2003), Image, style and status: A sketch of the role and impact of private enterprise as a commissioner on architecture and urban development in the Dutch East Indies from 1870 to 1942, Journal for South East Asian Architecture

- van Roosmalen, Pauline K.M. (2003), We zullen het ze vertellen’. Het vergeten Indische werk van Nederlandse architecten, Laverend op koers, BONAS, Rotterdam

- Silver, Christopher, (2008) Planning the Megacity: Jakarta in the Twentieth Century, Routledge Publishers

Credits

Created by

Map designed by

About

Begandring Soerabaia

A social, cultural and heritage community collective that is keen on discovering and sharing cultural and historical issues.

www.facebook.com/begandringSurabaya Memory

Surabaya Memory is an initiative of the Petra Christian University with an impressive digital library and research centre on Surabaya's heritage

@surabaya.memoryCelcea Tifani Celcea Tifani

Celcea is a young and happy designer, researcher and wanderer of the streets of Surabaya. Celcea merupakan seorang peancang muda ceria dan petualang jalanan Surabaya.

@pertigaanmap